Researchers at Imperial College London report that the gut microbial metabolite trimethylamine (TMA) reduced low‑grade inflammation and improved insulin responsiveness in mice and human tissue models, potentially lowering type 2 diabetes risk. Biochemical analyses indicate TMA inhibits the kinase IRAK4, a trigger for diet‑linked inflammatory signalling. Although promising, these early findings require confirmation in longer human trials before clinical application.

Gut Microbe Molecule Trimethylamine May Lower Type 2 Diabetes Risk by Blocking Inflammation

New research led by Imperial College London suggests a small molecule produced by gut bacteria — trimethylamine (TMA) — could help protect against some harms of a high‑fat diet that lead to type 2 diabetes.

What the Study Found

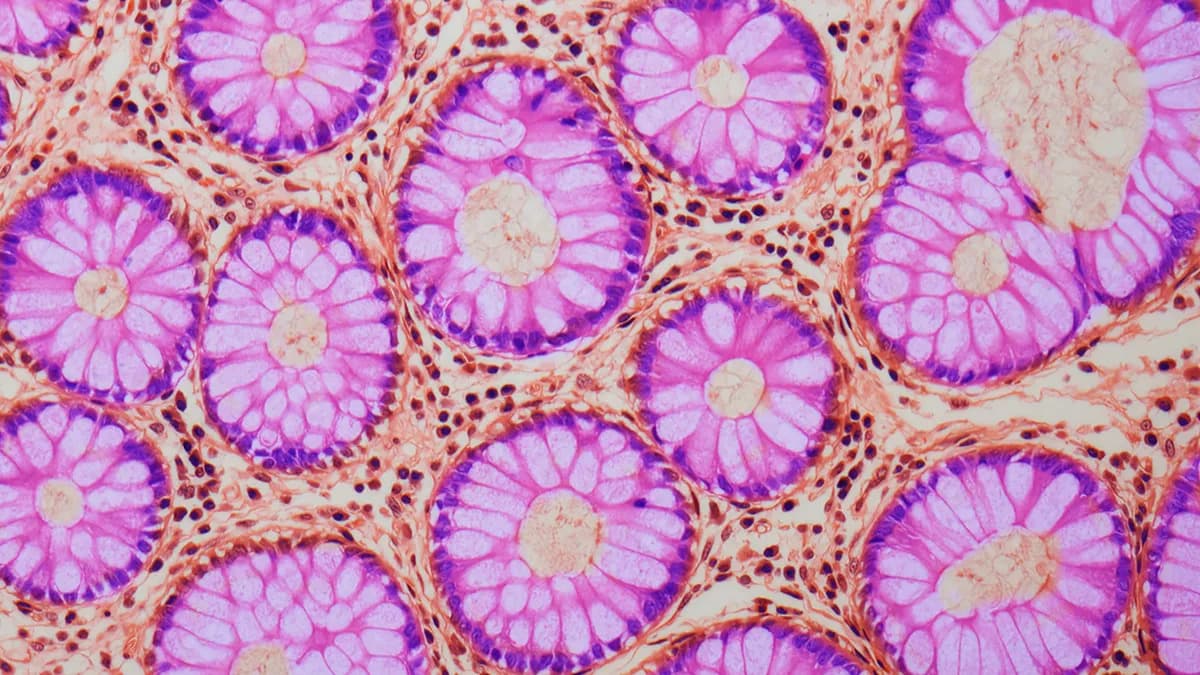

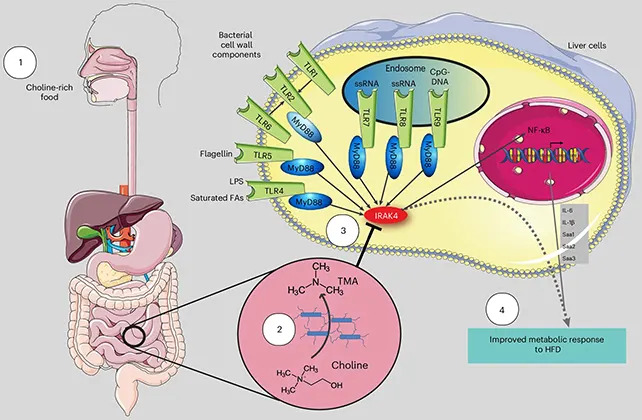

TMA is a common bacterial metabolite created when gut microbes break down choline, a nutrient found in foods such as eggs, meat and some vegetables. Using human cell models and experiments in mice, researchers report that TMA reduced low‑grade inflammation and improved insulin responsiveness — two factors that can lower the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

How TMA Works

The team identified the kinase IRAK4 as a likely biochemical target: TMA appears to inhibit IRAK4, a signalling protein that normally helps trigger an inflammatory response to a high‑fat diet. By dampening this pathway, TMA interrupted links between obesity, chronic inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in the laboratory models.

"This flips the narrative," said ICL biochemist Marc‑Emmanuel Dumas. "We've shown that a molecule from our gut microbes can actually protect against the harmful effects of a poor diet through a new mechanism."

Context And Cautions

Earlier studies connected TMA and its oxidized derivative trimethylamine N‑oxide (TMAO) with higher cardiovascular risk, so the new findings complicate the picture — indicating that under some conditions TMA may have beneficial metabolic effects. The researchers stressed that the protective effects have so far been shown in mouse models and human tissue experiments, and must be confirmed in longer human clinical trials before any treatment recommendations are made.

"In view of the growing threat of diabetes worldwide and its devastating complications for the whole patient, including the brain and heart, a new solution is direly needed," said cardiologist Peter Liu of the University of Ottawa. He added that the study linking Western‑style foods, microbiome‑produced TMA and the immune switch IRAK4 could open new avenues to prevent or treat diabetes.

Implications

The study, published in Nature Metabolism, highlights a broader principle: gut bacteria produce small molecules that can interact with and regulate host kinases — molecular switches that control many biological pathways. This raises the possibility of developing microbiome‑based therapies that target kinases to treat or prevent obesity‑related inflammation and metabolic disease.

Next Steps: Researchers plan further studies to replicate these results in humans over longer periods, and to better understand when TMA is protective versus when its derivatives may increase cardiovascular risk.

Help us improve.