MIT researchers analysed dry pre‑mix materials from a 79 CE Pompeii worksite and found tiny quicklime "lime clasts" and evidence of "hot‑mixing," an exothermic process that produced slaked lime. Those undissolved lime clasts can react with water if cracks form, precipitating material that helps seal fractures—effectively allowing the concrete to self‑heal. While the discovery revises assumptions about Roman manufacturing, it is based on a single well‑preserved context and further sampling is needed to determine how widespread the technique was.

Pompeii Discovery Rewrites Our Understanding Of Roman Self‑Healing Concrete

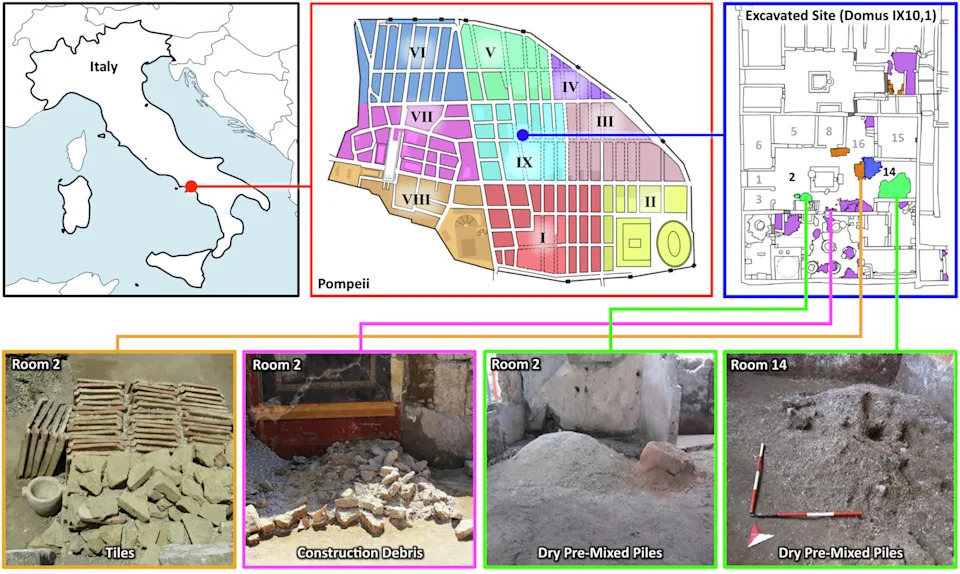

Roman concrete helped preserve temples, baths, bridges and roads for millennia, yet many details of how ancient builders produced such durable mortar have remained unclear. A new study led by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and published in Nature Communications uses materials left at an abandoned Pompeii worksite (buried in the 79 CE eruption of Mount Vesuvius) to reveal how Romans prepared what appears to be a self‑healing concrete.

Rare Pre‑Mix Materials Offer a Window Into Ancient Practice

Archaeologists uncovered a partially constructed house in Pompeii with dry, pre‑mix stocks: tiles set aside for recycling, amphorae reused to carry construction materials, and piles of powdered components intended for later mixing. Because these materials were preserved before water was added, researchers had a rare chance to analyse the raw ingredients and reconstruct the mixing process.

Hot‑Mixing, Quicklime And Lime Clasts

Chemical and microstructural analysis identified very small particles of quicklime (calcium oxide) in the dry mix. Quicklime is produced by heating high‑purity limestone (calcium carbonate). The team argues that workers combined ground lime with pozzolana (a volcanic ash) in the house's atrium. When water was later added, the reaction released heat—an exothermic process known as "hot‑mixing."

As quicklime converts to slaked lime it normally dissolves, but the researchers found undissolved micro‑fragments they call "lime clasts". These clasts retain reactive quicklime properties: if the concrete later cracks and water reaches exposed clasts, the lime can react and precipitate materials that help close or heal the fissure. In short, the mix shows a clear mechanism for self‑healing mortar.

Context, Comparisons And Caution

The Pompeii find complements ancient textual sources. Vitruvius recommended mixing pozzolana with lime but did not explicitly describe hot‑mixing; Pliny the Elder does record the heat released when quicklime meets water, indicating contemporary awareness of the chemistry. The MIT team previously identified similar lime clasts at Privernum, about 43 kilometres north of Pompeii, and healed crack behaviour has been observed at the tomb of Caecilia Metella on the Via Appia, suggesting the phenomenon may not be unique to Pompeii.

Nevertheless, the authors emphasise caution. The Pompeii assemblage is a single, well‑preserved snapshot. It is not yet possible to say how widespread hot‑mixing and lime clasts were across space and time in the Roman world. Roman writers themselves often warned that poor mortar caused building failures, so capacity and consistent practice are not the same thing.

Questions That Remain

Key open questions include whether hot‑mixing was a common practice, whether mixes varied intentionally in seismic regions to promote self‑healing, and how often healed fractures can be identified in surviving Roman mortar. Systematic sampling and microstructural analysis across many sites will be needed to answer these questions.

Note: This article summarises and adapts research reported in Nature Communications and is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence.