The Pacific is still in a weak La Niña, but forecasters expect it to fade by February and move to ENSO-neutral. A very warm pool in the western Pacific — among the warmest since 1950 — could fuel a rapid shift to El Niño if strong westerly wind bursts push that heat east. Historical experience (spring 2014) shows winds can halt development, so the next few months are critical. Observers will watch tropical surface winds and the Niño-3.4 index for signs of a basin-wide shift.

Could the Pacific Flip From La Niña to El Niño by Summer 2026? What Scientists Are Watching

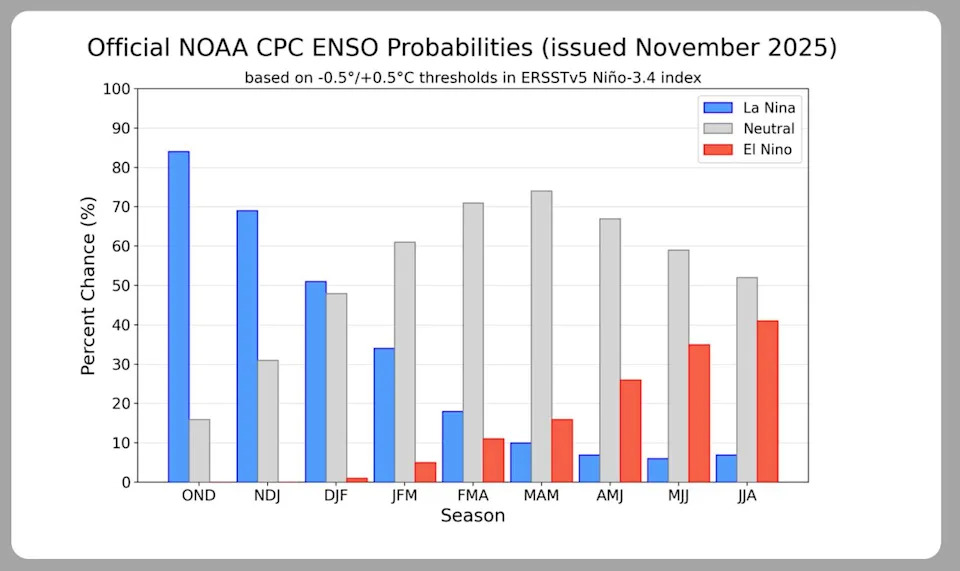

The Pacific Ocean remains officially in a weak La Niña, but the forces holding that pattern together are weakening and forecasters say the phase will likely fade by February. On Thursday the U.S. Climate Prediction Center (CPC) kept a La Niña Advisory in place, confirming continued cool sea surface temperatures in parts of the equatorial Pacific.

Forecasters expect La Niña to wane and ENSO (El Niño–Southern Oscillation) to move toward a neutral state within a couple of months. However, growing evidence suggests that neutral conditions may be short-lived and the basin could swing back to El Niño as early as next summer if atmospheric conditions change.

"There is high confidence that we currently are at or near the peak of this weak La Niña, so we expect that ocean temperatures in the eastern equatorial Pacific will rise and bring us to ENSO-neutral within a couple of months," said Nat Johnson, a meteorologist at the NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory.

NOAA's primary tracking metric, the Niño-3.4 index, measured about -0.5°C in the first week of December — right at the conventional threshold used to define La Niña conditions. That borderline value underscores how marginal the current La Niña is.

Why A Rapid Flip Is Possible

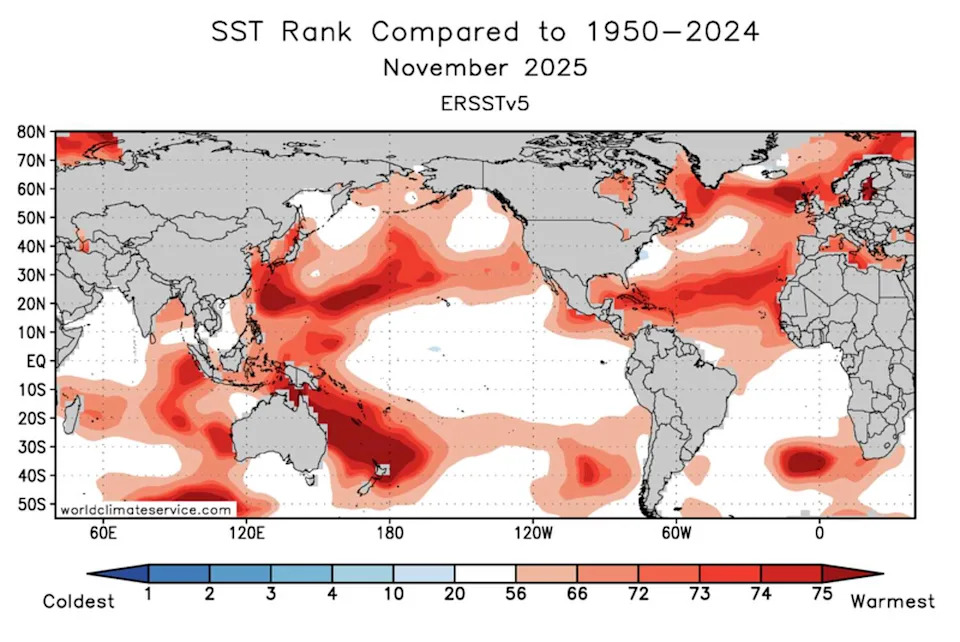

During La Niña, persistent easterly trade winds push warm surface water westward, building a large pool of unusually warm water in the western Pacific. That warm pool is now among the hottest recorded since 1950 and represents a substantial store of thermal energy.

Short, strong pulses of westerly winds — called westerly wind bursts (WWBs) — can push that warm western water back toward the central and eastern Pacific. If WWBs are strong and sustained, they can trigger a rapid basin-wide warming and flip the Pacific into an El Niño.

Fuel Versus Trigger

Having a large warm reservoir is necessary but not sufficient for El Niño to form. Atmosphere–ocean interaction, especially the direction and strength of surface winds, determines whether stored heat is mobilized. "I think it's a bit too early for the event to be sufficient by itself to kick off El Niño," Johnson said.

As a cautionary example, spring 2014 showed a similar pattern — a western warm pool and early westerly bursts hinted at a strong El Niño. But easterly winds later prevailed, stalling development and delaying El Niño by about a year. That "false start" is a reminder that the coming months are decisive.

Potential Impacts

If the Pacific does shift quickly to El Niño by next summer, global weather patterns would likely be affected: higher odds of a warmer-than-average end to 2026 in many regions, shifts in precipitation patterns, and an increased chance of weather extremes in some areas. For California, El Niño often brings wetter conditions, but local outcomes vary and the relationship has shifted in recent years.

Scientists will be closely monitoring tropical surface winds over the next few months. If strong westerly wind bursts recur and the tropical atmosphere responds, the probability of an El Niño rise sharply.

What To Watch: Niño-3.4 index trends, frequency and strength of westerly wind bursts, and signs of atmospheric coupling (convection changes) across the tropical Pacific.