Key finding: Repeated question‑mark grooves on ancient bivalve shells were matched to modern spionid bristle worms, revealing a parasitic behavior that persisted from the Ordovician (≈485–444 Ma) to today. Using micro‑CT scans and literature comparison, researchers showed stacked fossils with identical burrow shapes and inferred a lifecycle in which larvae settle, erode shell, and burrow inward. Published in iScience (2025), the study highlights parasitism as a long‑lived ecological strategy.

The Worm That Defied Extinction: Bristle Worms Left Question‑Mark Fossils for 500 Million Years

The Worm That Defied Extinction

Worms may seem fragile, yet a group of marine bristle worms has left a remarkable fossil record that stretches back nearly half a billion years. Paleobiologists have matched recurring, question‑mark‑shaped grooves on ancient bivalve shells to the feeding and burrowing activity of modern spionid worms, showing that this parasitic lifestyle persisted from the Ordovician to the present.

How researchers solved the mystery

Karma Nanglu of the University of California, Riverside, and colleagues were examining fossil bivalves when they noticed a recurring, curious groove etched into multiple shells. As they investigated museum collections at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, Javier Ortega‑Hernandez and others recognized the same signature pattern. "It took us a while to figure out the mystery behind these peculiar‑looking traces," Ortega‑Hernandez said. A match in the literature — an image of a modern worm producing the same mark — provided the decisive link.

Imaging and evidence

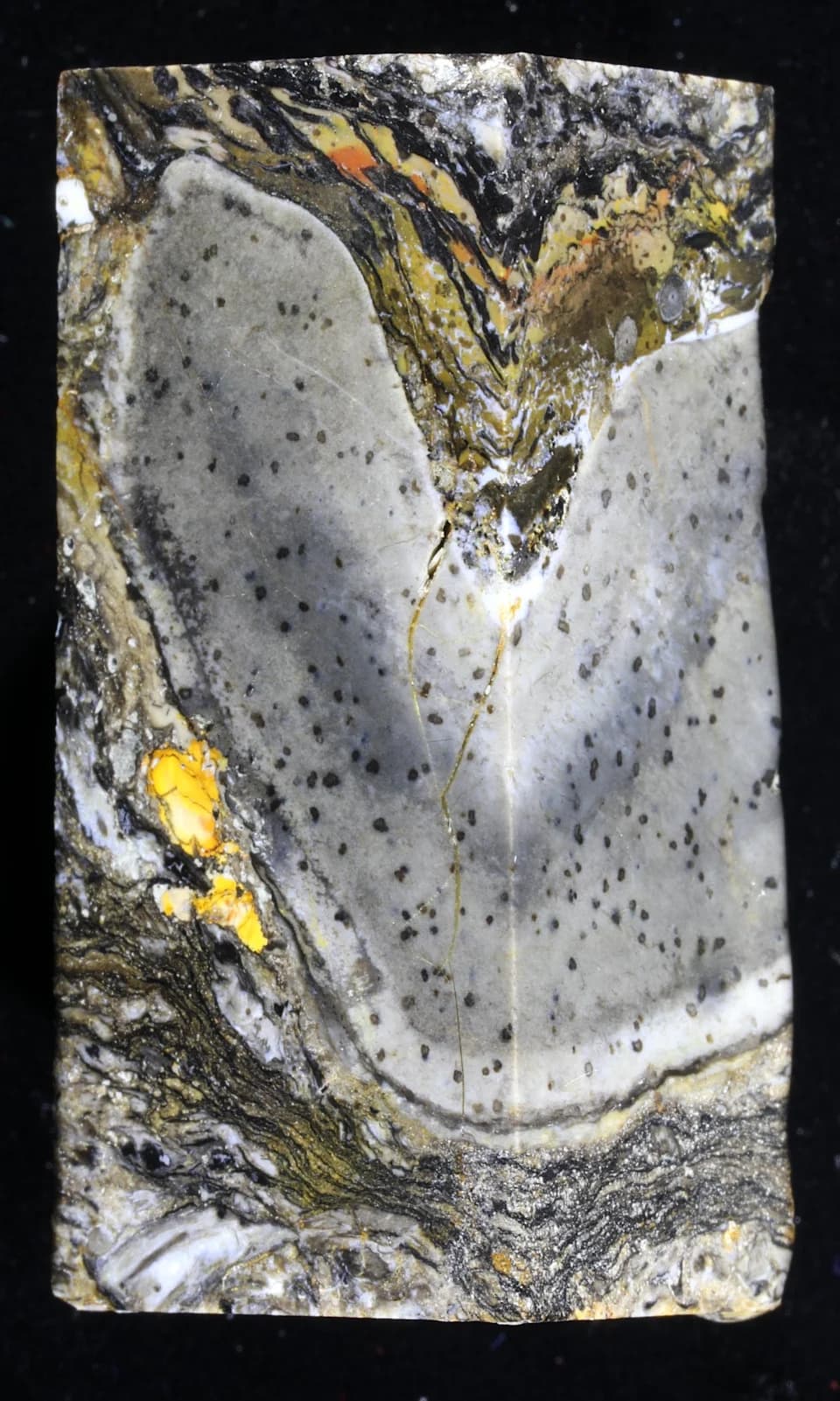

The team used micro‑CT scanning to visualize the grooves in three dimensions. The scans revealed stacked, infected bivalves with identical burrow shapes preserved through multiple layers of sediment. These repeated, question‑mark‑shaped traces pointed to a consistent behavior pattern across individuals and geological time.

What the traces mean

The traces are attributed to spionid bristle worms, soft‑bodied polychaetes bearing tiny bristles along their bodies. Spionids feed on mussels and oysters by rasping and burrowing into shells; their larval stages likely settled on a host, eroded a small amount of shell, then tunneled inward, producing the characteristic curved groove. Among known animals, spionids are uniquely associated with these question‑mark burrows.

"This parasite didn’t just survive the cutthroat Ordovician period, it thrived," said Nanglu. "It’s still interfering with the oysters we want to eat, just as it did hundreds of millions of years ago."

Why it matters

These findings, published in iScience (2025), show that parasitism can be an exceptionally resilient ecological strategy. Despite mass extinctions and dramatic environmental change over hundreds of millions of years, this lineage maintained its ecological niche and left a distinctive, traceable record in the fossil record. The study highlights how behavioral traces can reveal long‑term persistence of interactions such as parasitism, not just the evolution of body forms.

Lead image: Nanglu, K., et al., iScience (2025).

This story was originally featured on Nautilus.

Help us improve.