The Central Sierra Snow Laboratory at Donner Summit maintains nearly 150 years of snow observations and combines twice-daily manual measurements with modern sensor masts, 3D-printed temperature rigs and dust monitors to improve forecasts of snowmelt and water supply. Recent storms produced heavy snowfall this season, while statewide surveys on Dec 30, 2025 put snowpack at 71 percent of average. Researchers warn warming is shifting precipitation from snow to rain and could significantly reduce Sierra snow by mid-century, with major consequences for California water resources.

Donner Summit's 150-Year Snow Record: UC Berkeley Lab Blends Tradition With Modern Science

The Central Sierra Snow Laboratory, run by UC Berkeley a few miles outside Truckee at Donner Summit, maintains one of the world's longest continuous snow records and is pairing that legacy with new instruments to improve forecasts of snowmelt and water supply.

A Long, Careful Record

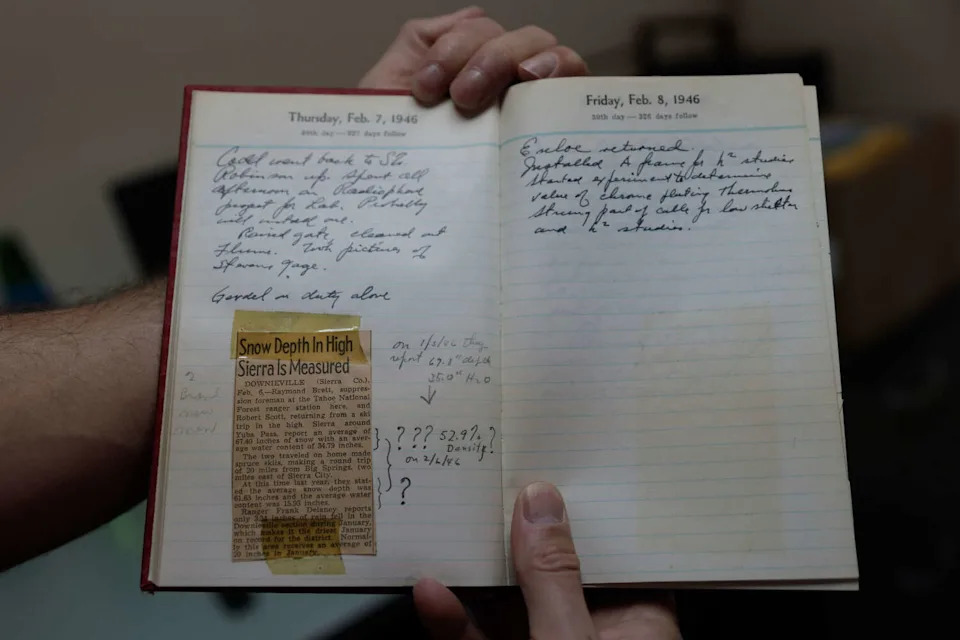

The site continues a measurement practice that stretches back nearly 150 years. Early snowfall observations by the Southern Pacific Railroad date to at least the winter of 1878-1879, and the permanent research station was established in 1946 through a collaboration between the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Weather Bureau, the predecessor of the National Weather Service. For decades staff have taken twice-daily snowfall measurements on a wooden board and analyzed samples for water content, creating an invaluable long-term dataset.

It is a cool way to keep one foot in the past, continuing this really long record, as well as trying to push the envelope on new science, said Gabe Lewis, a research scientist at the lab.

From Simple Tools to Sophisticated Sensors

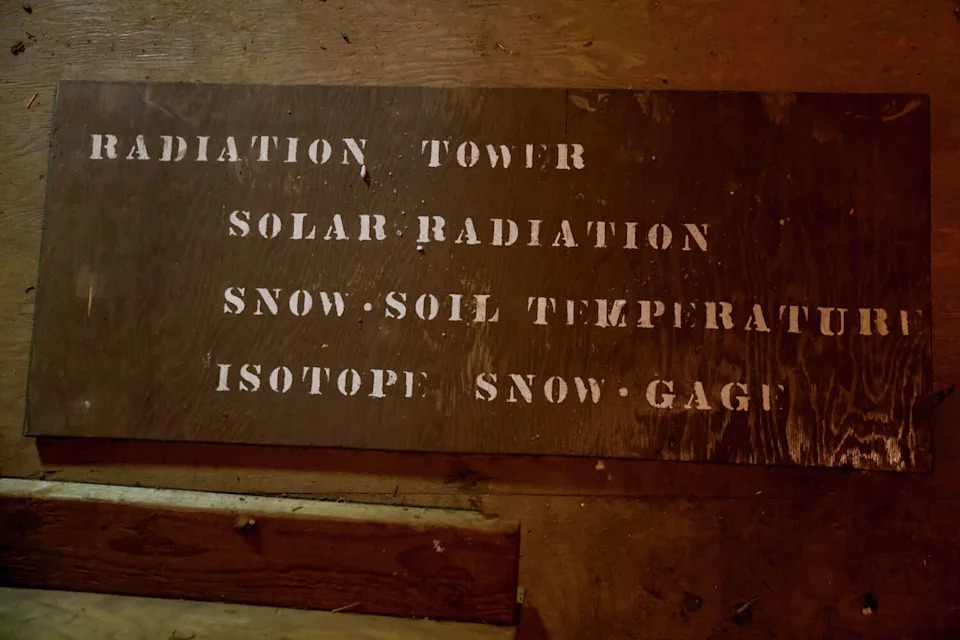

Although the core measurement remains intentionally low-tech, the lab now houses modern instruments that deliver deeper physical insight. Their newest automated mast, which resembles a parking-garage gate arm, holds sensors at a fixed height and rises as snow accumulates. Those sensors measure incoming solar radiation, reflected light (albedo), longwave radiation, and turbulent heat exchange between the atmosphere and the snow surface, all critical components of the snowpack energy balance.

Researchers are also deploying an innovative 3D-printed rig of temperature sensors designed to be buried by accumulating snow. The vertical temperature profile it provides will, for the first time, be ingestible directly into snow models to sharpen predictions of melt timing, streamflow and flood potential.

Other work includes airborne dust measurements. Dust particles serve as cloud condensation and ice nuclei, influencing precipitation and snow albedo. Lab researchers are combining field observations with high-resolution computer models to test whether adding condensation nuclei to clouds could increase precipitation in some storms.

Field Experiments and Real-World Context

The lab is also testing whether typical measurement sites tell the whole story. Historically, snow courses were placed in open meadows. To compare conditions, researchers installed an instrument tower amid trees to quantify how snow accumulation and melt differ in forested settings, where daily temperature swings can be smaller and snowpack processes may diverge from meadow measurements.

Recent Seasons, Staff and Capacity

This season the lab recorded more than 20 inches of snow in a single day during a major storm that caused hazardous driving and highway closures around Lake Tahoe. Since Oct 1, 2025 the station had logged 9.6 feet of snow, and a separate storm around Christmas brought more than four feet to the area.

The 2022-2023 season was one of the snowiest on record at the station, with more than 62 feet measured, the second-snowiest season in the lab's history. Lab director Andrew Schwartz estimates he shoveled roughly 330,000 pounds of snow that year.

When Schwartz joined the lab in 2020 it had a single full-time employee, slow internet and a roughly $100,000 annual budget. Grants and additional UC Berkeley support have since increased funding by several hundred thousand dollars, allowing the team to expand. Current personnel include Andrew Schwartz, Gabe Lewis, Megan Mason, Marianne Cowherd and Kiana Tsao, and new towers and equipment now occupy a clearing behind the station.

Why This Matters

Long records give scientists and water managers context for today’s conditions. As Benjamin Hatchett, an earth system scientist at Colorado State University, noted, these records help answer questions such as when a given event last occurred and whether it has happened before. California depends on Sierra snowpack as a natural reservoir, and scientists warn that warming is shifting more precipitation from snow to rain. Climate projections indicate parts of the Sierra could experience little to no snow by mid-century under some scenarios, with serious implications for water supply.

At California's first statewide snow survey of the season on Dec 30, 2025 officials reported that statewide snowpack water content was 71 percent of average for the date. The Central Sierra Snow Laboratory was one of 111 stations used in the statewide calculation.

Collecting good data on the statewide snowpack is not easy, wrote David Rizzardo, manager of the California Department of Water Resources hydrology section. DWR's long-term relationship with the Central Sierra Snow Lab is critical for exploring new methods to collect the data we need to forecast the state's water supply accurately.

Looking Ahead

Schwartz hopes to expand the lab's research portfolio, bring more students to the site, and eventually establish a public center to share the lab's history and science. The combination of an exceptionally long observational record and new measurement technology positions the lab to track climate-driven changes to Sierra snowpack in real time and to help water managers prepare for a changing future.

Help us improve.