Summary: After a national Royal Commission exposed mishandled abuse cases — including the Frank Houston scandal — Australia’s largest Assemblies of God body required affiliated churches to adopt mandatory child-protection measures such as reporting, background checks and credentialing. The U.S. Assemblies of God, overseeing about 13,000 autonomous churches, promotes safety practices but has declined to impose national rules, citing local autonomy and legal liability concerns. Advocates praise Australia’s steps but warn enforcement gaps and survivor compensation remain unsettled.

Australia Mandated Child-Safety Rules for the Assemblies of God — Why the U.S. Still Resists

The Assemblies of God in Australia moved decisively after a national inquiry exposed systemic failures to protect children. In 2015 the country's largest Assemblies of God network required affiliated churches to adopt minimum child-protection measures — including mandatory reporting, reference checks for all staff and volunteers, and credentialing for anyone called a "pastor." By contrast, the Assemblies of God in the United States continues to urge local churches to adopt safety policies but refuses to impose them nationwide, citing congregational autonomy and legal concerns.

What Australia did and why

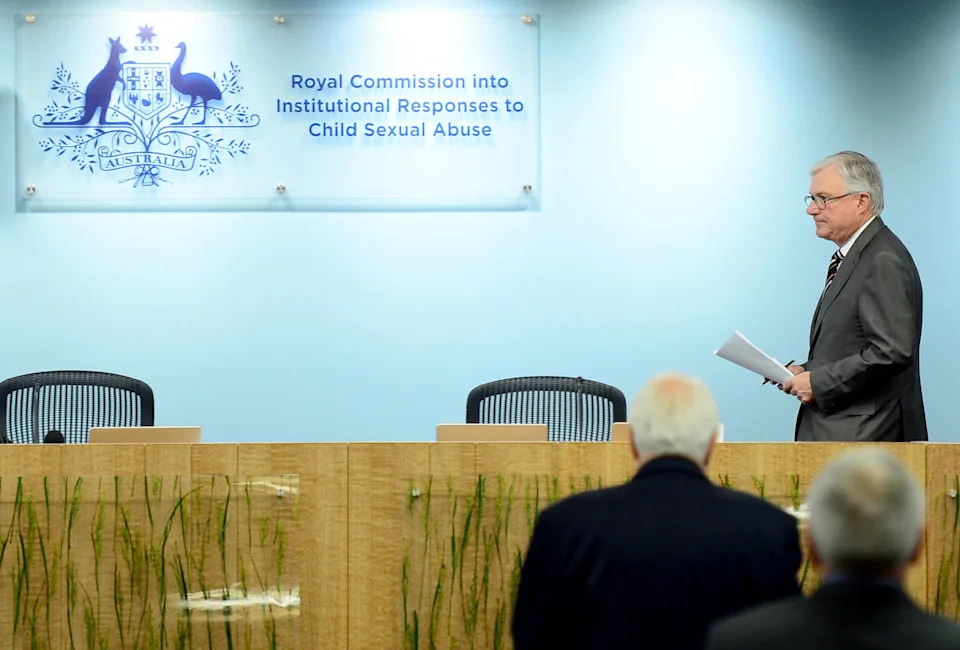

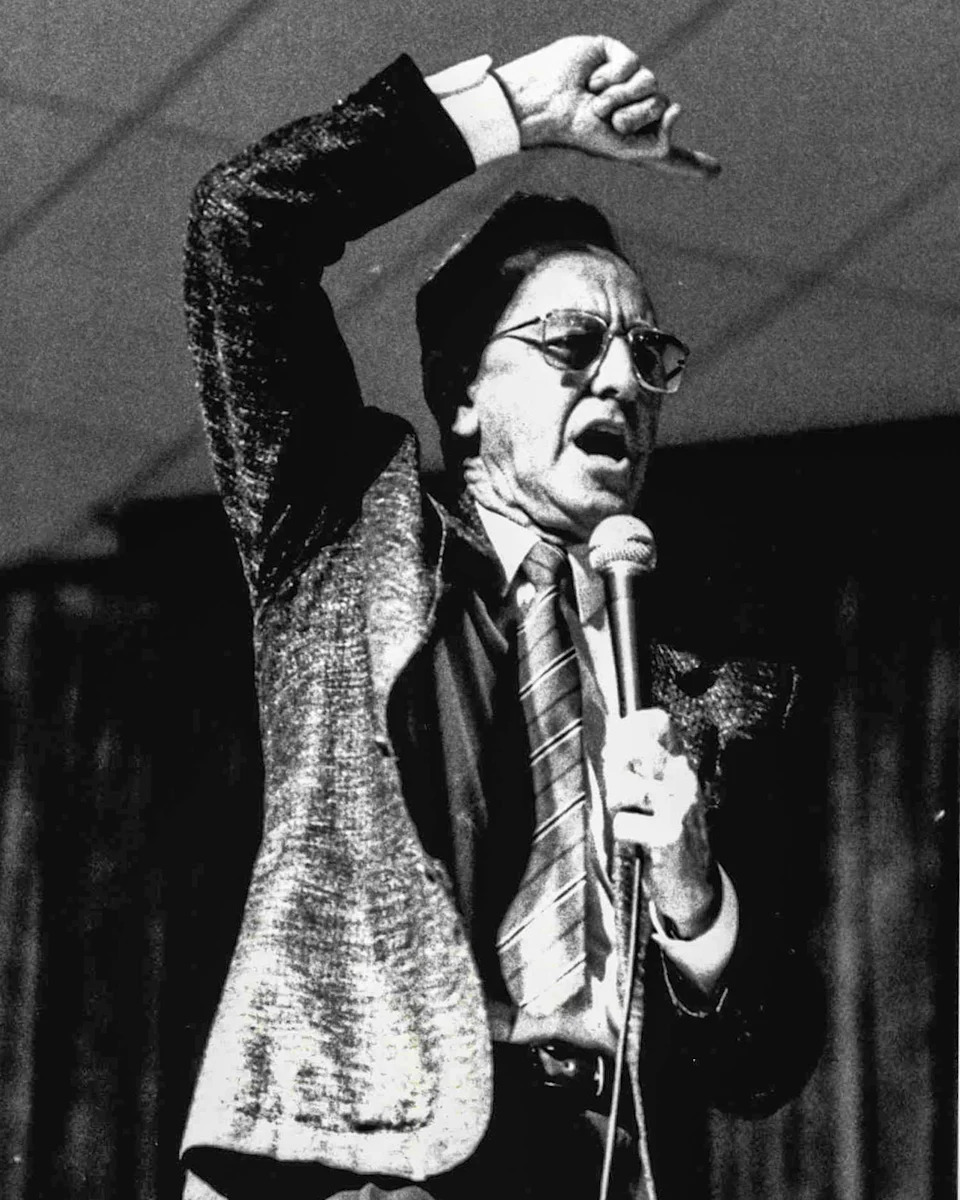

Australia's reforms were driven in large part by the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (2013–2017), a sweeping, government-led inquiry that examined how religious and secular institutions handled abuse. The commission found the denomination had prioritized protecting pastors over children in several high-profile cases, most notably the decades-old abuse by Frank Houston and the subsequent mishandling of that case by church leaders.

Under pressure from the commission and public outrage, Australian Christian Churches — the country’s largest Assemblies of God body, representing more than 1,100 churches — adopted mandatory minimum policies. These require affiliated congregations to implement mandatory reporting of suspected child abuse, conduct reference and criminal-background checks for all staff and volunteers, and ensure anyone described as a "Pastor" is credentialed by the national body. The denomination also engaged an independent child-protection organization, Creating Safer Communities, to help draft policies and operate a national safety hotline.

The U.S. response: encouragement, not mandates

The General Council of the Assemblies of God in the United States emphasizes child safety, offers recommended training and requires background checks for credentialed senior pastors, but stops short of mandating uniform policies across roughly 13,000 autonomous churches. Leaders say they lack the authority to force compliance and worry that a national mandate could increase legal exposure for the denomination.

Proposals to require national child-safety rules were considered by the General Council in 2019 and again in 2021 but were rejected; General Secretary Donna Barrett warned a mandate could play "right into the hands of plaintiffs' attorneys." Critics say that concern about liability and a devotion to congregational independence have left gaps that allow abusers to move between churches.

Patterns, investigations and survivors' accounts

An NBC News investigation identified about 200 Assemblies of God pastors, employees and volunteers accused of sexual abuse over the last 50 years. Reporting and survivor testimony across multiple countries — including allegations in England, Nicaragua and Argentina — paint a picture of recurring problems: accused leaders sometimes retained roles of authority, were reassigned, or were allowed to retire quietly without referral to police.

“There’s just no oversight or accountability anywhere — it’s up to each leader how they want to address it,” said Jen Doyle, who says she was abused as a teenager in an Assemblies of God church in Pennsylvania. “The victims are the ones that are going to suffer the worst.”

Limits of the Australian reforms and ongoing concerns

Survivors and advocates in Australia welcome the policy changes but note important limits. Australian Christian Churches requires local sign-off on policies but does not publish a transparent audit process to verify compliance, and questions remain about enforcement and discipline of noncompliant churches. Some survivors who sought compensation have also faced legal pushback; a notable lawsuit by a survivor who helped convict his abuser was dismissed when the denomination argued it lacked control over member churches at the time of the abuse.

Why the difference matters

The contrast between Australia and the U.S. highlights how institutional structure, public scrutiny and legal pressure shape organizational responses to abuse. Australia’s national inquiry forced a public accounting and concrete reforms; in the United States, the combination of decentralized governance and concerns about liability has so far prevented a similar, binding nationwide response within the Assemblies of God.

The debate continues about how best to protect children while balancing church autonomy and legal risk. Survivors, advocates and some former ministers argue that uniform standards, rigorous enforcement, transparent reporting and independent oversight are necessary to prevent future harm — and to rebuild trust in religious institutions.