Sediment analysis from Vindolanda, a Roman fort near Hadrian's Wall, uncovered roundworm and whipworm eggs and — for the first time in Roman Britain — DNA evidence of Giardia duodenalis. Parasite eggs were present in 28% of sewer samples, implying regular fecal‑oral transmission despite Roman sanitation features like latrines and an aqueduct. The infections are consistent with chronic diarrhea, anemia and fatigue, which likely reduced soldier fitness. The study, published in Parasitology, highlights how local social and environmental factors shaped parasite exposure in Roman communities.

Gut Reactions at Vindolanda: Parasites and Giardia Reveal Widespread Illness Among Roman Soldiers

Archaeological analysis of sediments from Vindolanda, a Roman fort near Hadrian's Wall in northern England, reveals that soldiers stationed there frequently suffered gastrointestinal infections. Excavations recovered eggs of parasitic roundworms and whipworms from sewer and ditch deposits, and for the first time in Roman Britain researchers detected DNA traces of Giardia duodenalis.

What the Team Did

A joint research team from Canada and the United Kingdom analyzed sediment from two contexts: a sewer drain linked to a latrine block at a third‑century bathhouse and a first‑century defensive ditch. Vindolanda’s excellent preservation — including wooden writing tablets, multiple bathhouses, an aqueduct, drains, and ditches — made it an ideal site to search for intestinal pathogens that spread via contaminated water, food, or hands.

Key Findings

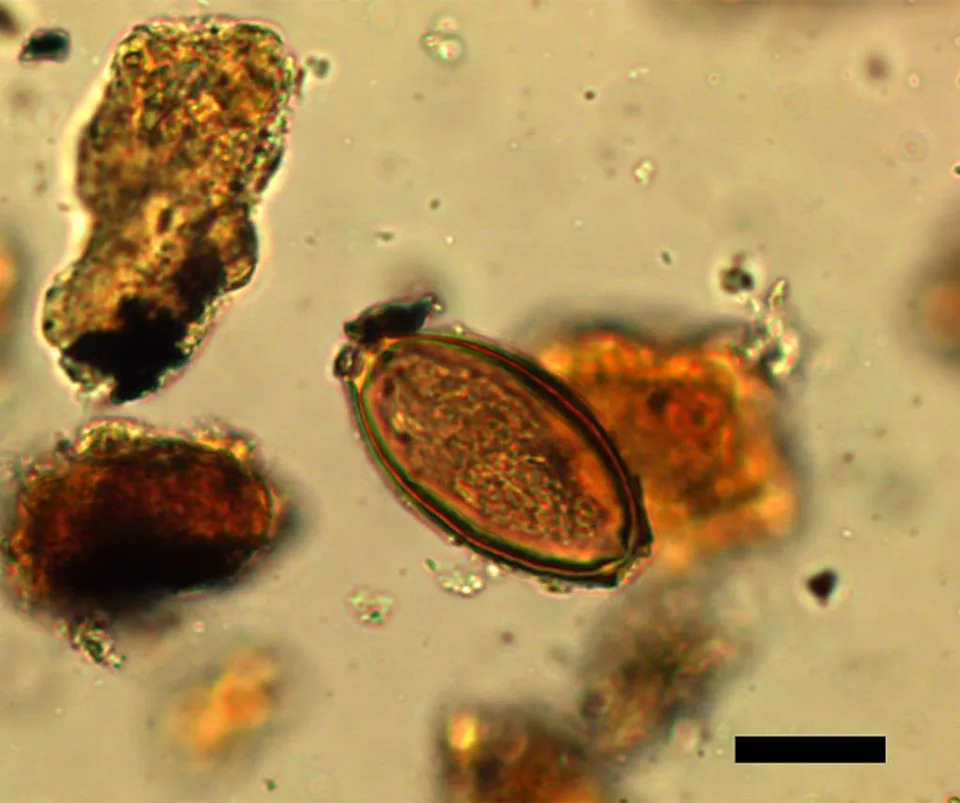

The investigators found eggs of roundworms (Ascaris-type) and whipworms (Trichuris-type) in samples from both the sewer and the ditch. Parasite eggs appeared in 28% of sewer drain samples. In one sewer sample the team also identified DNA from Giardia duodenalis, the first documented occurrence of this parasite in Roman Britain. These parasites are associated with symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, fatigue, anemia, dehydration and weight loss.

Marissa Ledger, a biological anthropologist at McMaster University and lead author while at the University of Cambridge, notes that the Romans were aware of intestinal worms but had limited medical options. Chronic infections, she says, likely weakened soldiers and reduced fitness for duty.

Interpretation and Broader Context

Although the fort had organized sanitation — latrines, drains and an aqueduct — the recovered parasites point to ineffective hygiene practices that allowed transmission to persist. Under such conditions troops would also have been vulnerable to other fecal‑oral pathogens such as Salmonella and norovirus.

Previous studies suggest differences between military sites and larger urban centers in Roman Britain: cities like York and London show evidence for a broader parasite community, including meat and fish tapeworms. The researchers argue these contrasts reflect a mix of social, cultural, dietary and environmental variables that shape transmission at local scales.

Overall, the new findings — published in the journal Parasitology — paint a picture of recurring gastrointestinal disease at Vindolanda that likely impacted the health and effectiveness of its garrison.