New excavations at Vindolanda and other sites along Hadrian’s Wall reveal the frontier as a lively, multicultural society rather than an isolated military line. Finds such as 1,700 ink tablets and roughly 5,000 shoe fragments document soldiers, families, merchants and enslaved people living and working together. The evidence highlights religious syncretism, long-distance recruitment, economic ties with local communities and both the hardships and ordinary routines of frontier life.

New Vindolanda Discoveries Rewrite Life on Hadrian’s Wall: A Bustling, Multicultural Frontier

Two millennia after Rome reached the limits of its power in Britain, new finds at Vindolanda and other sites along Hadrian’s Wall are transforming our view of life on the empire’s northern frontier. Far from a lonely, all-male military outpost, the archaeological record reveals a dynamic, multicultural community of soldiers, families, merchants, enslaved people and worshippers from across the Roman world.

Vindolanda: A Window Into Everyday Frontier Life

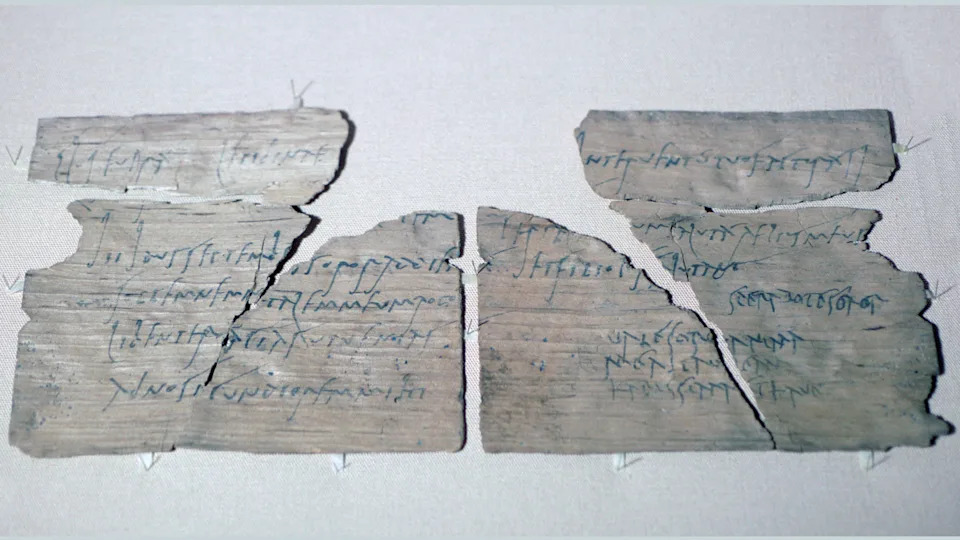

Vindolanda, a fort in today’s Northumberland that was demolished and rebuilt nine times, has produced exceptionally rich evidence. Archaeologists have recovered about 1,700 ink-written wooden tablets dating to around A.D. 100, roughly 5,000 leather shoe fragments from Vindolanda and the nearby fort Magna, and a range of household objects, inscriptions and building remains that illuminate daily routines and social life.

What the Tablets and Shoes Tell Us

The Vindolanda tablets provide intimate snapshots — from supply orders and financial notes to personal letters. One famous letter from Claudia Severa invites Sulpicia Lepidina to a birthday celebration and represents the earliest known female handwriting in Latin. Thousands of shoe fragments identify men, women and children living at or near the fort and even suggest how people coped with cold weather.

Families, Civilians and Social Complexity

Early scholars imagined isolated garrisons of unmarried soldiers. Excavations have overturned that view. Evidence shows auxiliaries commonly lived among families and civilians: extramural settlements (civilian neighborhoods outside the fort) existed alongside life inside the walls. Officers’ families — and in many cases lower-ranking soldiers’ families — contributed to an open, interwoven community.

Slavery, Commerce and Cultural Exchange

Recent work has also increased evidence for enslaved people on the frontier. A newly deciphered tablet records a deed of sale for an enslaved person, and inscriptions such as the Regina Tombstone from Arbeia commemorate enslaved individuals. Merchants and local entrepreneurs clustered around forts, supplying food, clothing and services; the Vindolanda tablets show money exchanges, contracts and routine provisioning.

Diversity of Origins and Beliefs

Auxiliaries were recruited from across the Roman Empire — places corresponding to modern Netherlands, Belgium, Spain and Syria — bringing varied customs and religious practices. Vindolanda shows religious syncretism: dedications to Roman gods such as Jupiter Optimus Maximus and Victory sit alongside local and hybrid deities, including a stone to Dea Gallia and a unique goddess named Ahvardua.

Violence, Health and Daily Drudgery

The frontier was not uniformly peaceful. Episodes like the brief occupation and abandonment of the Antonine Wall and the bloody campaign of Septimius Severus (A.D. 208) underscore periods of heavy violence. Yet most evidence points to everyday concerns — preparing for storms, gardening, sending socks to a comrade — alongside less pleasant realities: parasite infections revealed in latrines and widespread bedbug infestations.

Diet, Trade and Long-Term Legacy

Scientific analyses suggest a meat-heavy military diet, particularly beef, supplemented by imported foods such as wine and fish sauces. Trade networks and provisioning arrangements likely connected local producers (including in Highland Scotland) with Roman garrisons, creating economic opportunities amid coercion. Although Rome formally withdrew around A.D. 410, Vindolanda continued to be occupied by Christian communities — possibly descendants of former soldiers — into the ninth century.

Bottom line: Hadrian’s Wall was not only a military barrier but also a vibrant, interconnected frontier society that mirrored the diversity and complexity of the Roman Empire.

Similar Articles

6,000 Years Beneath Westminster: Stone‑Age Tools, Roman Relic and Medieval Walls Unearthed

Archaeological investigations at the Palace of Westminster have revealed artefacts spanning about 6,000 years, from Stone Age...

Mesolithic Flints and a 12th‑Century Hall Found Beneath Parliament — New Finds Reframe Central London’s Early History

A three‑year archaeological dig beneath the Palace of Westminster has uncovered artefacts dating from the Mesolithic (around ...

Shattered Skull at La Loma Suggests Romans Displayed Severed Head as Siege Warning

Archaeologists recovered a shattered skull beneath the collapsed walls of La Loma and conclude it likely belonged to a Cantab...

Roman 'Piggy Banks' Filled With Tens Of Thousands Of Coins Unearthed In French Village

Archaeologists excavating in Senon, northeastern France, uncovered three amphorae buried beneath a house floor that may conta...

16 Massive Pits Near Stonehenge Confirmed as Neolithic — A 1.25‑Mile Monumental Circle

Researchers have confirmed that 16 large pits around Durrington Walls, just north of Stonehenge, were intentionally dug durin...

Archaeologists Uncover Royal Palace Remains on Alexandrium, Revealing Herodian Architecture

The Alexandrium fortress, perched about 650 metres above the Jordan Valley, has yielded remains of a newly identified royal p...

Roman Trophy at La Loma: Shattered Skull Reveals Brutality of the Cantabrian Wars

The fragmented skull recovered at La Loma in northern Spain dates to the Cantabrian Wars and belongs to a man of local Iberia...

Roadwork Uncovers Nine Viking-Age Sites — Chieftain Pyre, Horse Burials and Everyday Farm Life Revealed

Road construction along Sweden’s E18 in Västmanland uncovered nine Viking-age sites, ranging from a mountaintop cremation com...

Archaeologists Unearth 11,000 Artifacts at Fones Cliffs — Sites Linked to John Smith’s 1608 Account

Archaeologists led by Julia King have recovered about 11,000 Indigenous artifacts at two Fones Cliffs sites along Virginia's ...

Ancient "Piggy Banks" in France Yield an Estimated 40,000 Roman Coins

Excavations in Senon, northeastern France, uncovered three amphorae buried in a house floor that together likely held more th...

Rich Roman Burial Unearthed in France: Bustum Pyre Yields 22 Gold Treasures

During routine development work in Lamonzie-Saint-Martin, INRAP archaeologists uncovered a Roman bustum containing the cremat...

Giant Neolithic Pits Around Stonehenge Confirmed As Human-Made — New Research Reveals Purposeful Layout

New research published in the Internet Archaeology Journal confirms that a ring of about 20 giant pits near Stonehenge — the ...

Massive Hasmonean Wall Unearthed: Over 40 Metres of Maccabean-Era Fortification Revealed at Jerusalem’s Tower of David

The Israel Antiquities Authority has exposed a more than 40-metre segment of a Hasmonean (Maccabean-period) city wall at Jeru...

Motorway Survey Uncovers 2nd‑Century B.C. Celtic Town Brimming with Gold, Amber and Pottery

During preconstruction surveys for the D35 motorway near Hradec Králové, archaeologists uncovered a large 2nd‑century B.C. Ce...

16 Roman Innovations That Still Shape Modern Life

The Roman world (1st century BC–5th century AD) introduced practical innovations in construction, public services and urban p...