Edinburgh’s Poet Laureate Michael Pedersen says the global custom of singing "Auld Lang Syne" at midnight grew organically from the song’s emotional resonance, not from any formal mandate. The Scots phrase means roughly "for old times' sake," and the song functions as a hymn of reunion that often involves joining hands and crossing arms in a communal circle. Robert Burns recorded the lyrics in 1788, though his exact role in creating the version we know is debated; publisher George Thomson later shaped the familiar tune. Pedersen has also added a modern poem, "Boys Holding Hands," celebrating friendship and emotional openness.

Why ‘Auld Lang Syne’ Still Brings the World Together at Midnight

Every New Year’s Eve, the familiar strains of "Auld Lang Syne" sweep across town squares, living rooms and wedding receptions — a ritual that, according to Edinburgh’s Poet Laureate Michael Pedersen, endures because the song binds people together rather than because anyone decreed it so.

An Organic Tradition

Pedersen, a prize‑winning Scottish poet, Writer in Residence at the University of Edinburgh and the city’s Makar, told CNN that singing the song at midnight on December 31 wasn’t ordained by ceremony or law. "For generations, it’s been sung at New Year because it’s perfect for it," he says. "People just had an emotional compass for it. They gathered outside town halls and sang it, and it drifted — like a great, beautiful glacier of song — into that New Year position."

Meaning and Melody

The Scots phrase auld lang syne roughly translates as "old, long since," and is commonly rendered today as "for old times' sake." Pedersen describes the song as a hymn of reunion: a look back at childhood friendships, renewed with a handshake and a shared drink. "It’s a song of reunion, not parting," he says. "It celebrates happy days gone by and the warm rush you feel when you come back together."

"It’s a mellifluous, song‑sized hug that’s survived the centuries." — Michael Pedersen

Performance as Ritual

Part of the song’s staying power is physical. Beyond the melody and words, there is choreography: people join hands, form a circle and — in many traditions — cross their arms to hold their neighbors’ hands. Pedersen notes that the arm‑crossing often happens later in the song: you hold hands through the verses, and then, around the climactic section in longer renditions, participants cross their arms and weave in and out of the circle. That shared movement creates a visible, communal expression of friendship.

Authorship and Adaptation

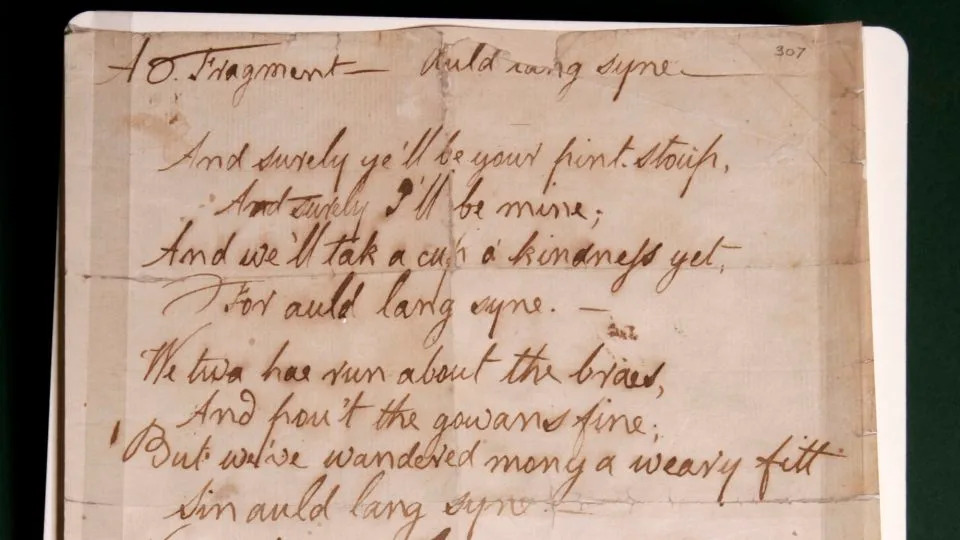

The song was first recorded by Robert Burns in 1788, but its exact origins remain a subject of debate. Burns himself said he had written down a version he heard in a coaching inn and adapted it. "We have no evidence of how much he adapted," Pedersen observes — it may have been a minor tweak or a substantial rewrite. After Burns’s death, publisher George Thomson further altered the music, shaping the tune that many recognize today. The result is a piece whose precise authorship is still a "beautiful, mellifluous mystery."

A Contemporary Addition

Pedersen has contributed his own poem to the New Year canon: "Boys Holding Hands," inspired by Burns and by a lifelong devotion to friendship. The poem also challenges restrictive norms of masculinity by advocating for emotional openness. "There’s a real bravado to masculinity that causes us to trap a lot of our emotions," he says. His poem invites men to let sentimentality and connection be visible and celebrated.

From a Scottish coaching inn to global midnight rituals, "Auld Lang Syne" has become an international act of remembering and reconnection — a short, shared ceremony that, year after year, pulls strangers and friends into a single, singing circle.