New research shows romaine lettuce leaf surfaces are chemically patchy at micro‑ and nanoscales. Atomic force microscopy reveals hydrophilic zones concentrated around stomata amid largely hydrophobic pavement cells. These water‑attracting patches likely promote rapid water loss and increase susceptibility to microbial contamination, helping explain why lettuce wilts and spoils quickly. Mapping such surface chemistry could guide postharvest treatments and breeding to extend shelf life and reduce food waste.

Why Lettuce Spoils So Fast — New Study Reveals Nanoscopic Weak Spots On Leaves

As children we learn that a leaf’s main jobs are photosynthesis — turning sunlight into chemical energy — and storing water. While those roles remain broadly true for edible leaves like lettuce, new research shows the leaf surface is far more complex than a uniform protective coat.

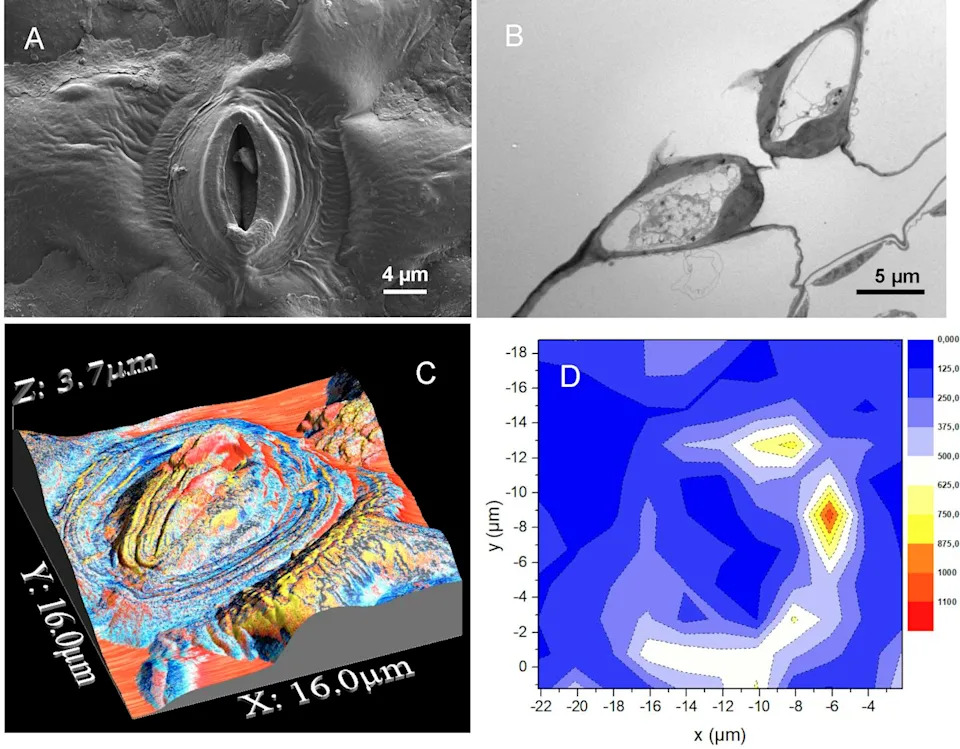

Researchers using atomic force microscopy (AFM) and other high-resolution techniques examined romaine lettuce at micro- and nanoscales and discovered that leaf surfaces are chemically patchy. Rather than a continuous, waterproof lipid layer, the cuticle presents alternating hydrophobic (water-repellent) and hydrophilic (water-attracting) zones concentrated around stomata — the tiny pores formed by pairs of guard cells.

What The Study Found

Pavement cells, which cover most of the leaf surface, are largely coated with hydrophobic lipids and behave like a water-repellent surface. Guard cells around stomata, however, show chemical heterogeneity: small hydrophilic patches embedded among hydrophobic areas.

This patchiness at the stomatal surface likely explains two practical problems with romaine lettuce: its rapid postharvest water loss and its vulnerability to microbial contamination. Hydrophilic zones provide pathways that facilitate water evaporation and can act as footholds for bacteria and viruses, accelerating wilting and spoilage.

Why It Matters

Understanding these nanoscale patterns opens up new opportunities to extend shelf life and reduce waste. If producers can target the hydrophilic hotspots — for example, with tailored coatings, careful humidity control, or breeding for different cuticle chemistry — it may be possible to reduce dehydration and microbial risks during storage, transport and display.

Broader Implications

Beyond lettuce, similar chemical heterogeneity has been observed on rose petals and olive leaves. This study is the first detailed chemical mapping of a horticultural species’ stomatal surface and suggests that mapping the micro- and nanoscale chemistry of fruits and vegetables could guide postharvest treatments, packaging design and breeding programs to strengthen food supply resilience.

Practical takeaway: The leaf’s ‘‘raincoat’’ is not uniform — tiny hydrophilic patches near stomata help explain why romaine wilts and spoils quickly. Addressing these hotspots could improve shelf life and reduce waste.

Study details: The research was conducted by teams at the Polytechnic University of Madrid, the University of Murcia and the University of Valencia using AFM and complementary methods to map chemical and physical properties of lettuce leaf surfaces.

Funding disclosures: Victoria Fernández carried out the study as part of a project financed by MCINN/AEI and the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR (project concluded September 2025). Ana Cros Stötter received funding from MICINN (ended September 2024). Jaime Colchero receives funding from MCINN/AEI and the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR through projects TED2021-130830B, PID2022-139191OB and PDC2023-145906.