The U.S. Air Force has pursued hypersonic aircraft for decades but remains in the experimental stage because aerodynamic heating and related effects create acute technical and safety problems. Surface temperatures near 3,500 °F at Mach 5 — and shock-layer temperatures above 10,000 °F at higher speeds — can melt metals and generate reactive gases that rapidly degrade materials. Only the Space Shuttle and the X-15 have flown crewed hypersonic missions, while unmanned vehicles like NASA's X-43 reached higher speeds but remained impractical. Engineers need significant advances in materials, thermal protection, and propulsion before practical hypersonic fighters become viable.

The Heat Problem: Why Hypersonic Jets Remain Out of Reach for the Air Force

"Hypersonic" denotes speeds above Mach 5 — about five times the speed of sound, roughly 3,800 mph. That velocity would carry an aircraft around the equator faster than a typical passenger jet can fly from New York to London, and it makes even the fastest supersonic fighters look slow. For decades the U.S. Air Force and NASA have chased hypersonic flight, but serious technical and safety obstacles have kept research largely in the testing phase.

Aerodynamic Heating: The Central Challenge

The principal barrier to practical hypersonic aircraft is aerodynamic heating. As speed increases, friction and shock waves raise surface temperatures dramatically: flight tests have recorded skin temperatures near 3,500 °F at Mach 5 — sufficient to melt titanium. Within the shock layer at higher hypersonic speeds, temperatures can exceed 10,000 °F, a regime that can overwhelm conventional metals and composites.

Why Extreme Heat Is So Dangerous

High-temperature gas chemistry compounds the engineering problem. Collisions in the shock layer can dissociate oxygen and nitrogen molecules, producing reactive radicals that accelerate oxidation and other destructive chemical reactions. Rapid heating and cooling cycles lead to repeated expansion and contraction, encouraging microcracks and structural fatigue. Together these effects shorten component life, undermine structural integrity, and present direct risks to crews.

Lessons From Past Tests

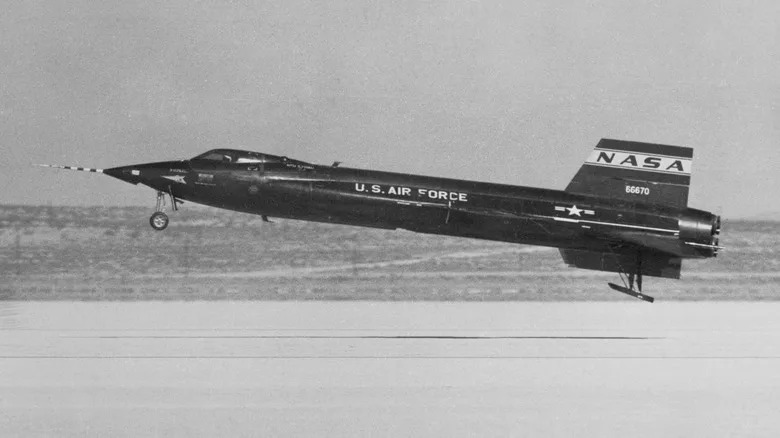

Only two crewed vehicles have reached hypersonic speeds in atmospheric flight: the Space Shuttle during reentry and the rocket-powered X-15 in the 1960s. Over 199 test flights the X-15 demonstrated remarkable performance — pilot Pete Knight reached Mach 6.7 (about 4,520 mph) in 1967 — but the program never produced an operational combat aircraft. The X-15 required a B-52 launch platform, burned its fuel in under two minutes, and behaved as a difficult-to-control glider after power-off; a fatal crash in 1967 ended the program.

Unmanned vehicles have achieved even higher peak speeds. NASA's X-43 reached Mach 9.6 in a 2004 flight, but like prior demonstrators it highlighted extreme inefficiency, fragility, and limited operational utility: only three test vehicles were built and one was lost. These high-speed successes demonstrate possibility but also underline how far engineering remains from a practical hypersonic fighter.

Paths Toward Solutions — And Their Limits

Engineers are pursuing several approaches to tame hypersonic heat: advanced high-temperature alloys and ceramic composites, thermal barrier coatings, active cooling systems, ablative materials, and novel structural designs. Propulsion options such as scramjets promise air-breathing hypersonic thrust but introduce their own thermal and control complexities. The Space Shuttle relied on an elaborate thermal protection system during brief reentry heating; sustaining controlled, crewed flight at hypersonic speeds inside the atmosphere would demand materials and systems far beyond current operational hardware.

Bottom line: Hypersonic flight remains a frontier of materials science, aerothermodynamics, and propulsion. Demonstrations have proven the speeds are achievable, but sustained, safe, and efficient manned hypersonic fighters will require breakthroughs in thermal protection, lightweight high-temperature structures, and reliable propulsion.

Sources: flight test data, historical X-15 and X-43 program records, NASA and public-domain reporting on aerodynamic heating and hypersonic materials challenges.