Amanda Mustard spent eight years making an HBO documentary about her grandfather, Dr. William Flickinger, who abused relatives and other children. After people told her she "should have killed" him, Mustard instead confronted him on camera and is calling for more prevention and reentry funding. She highlights that 15% of U.S. adults report childhood sexual abuse and that most victims knew their abuser, and she notes a large gap between spending on incarceration and prevention research.

Filmmaker Confronts Her Predator Grandfather On Camera After Being Told She 'Should Have Killed' Him — Calls For Prevention Funding

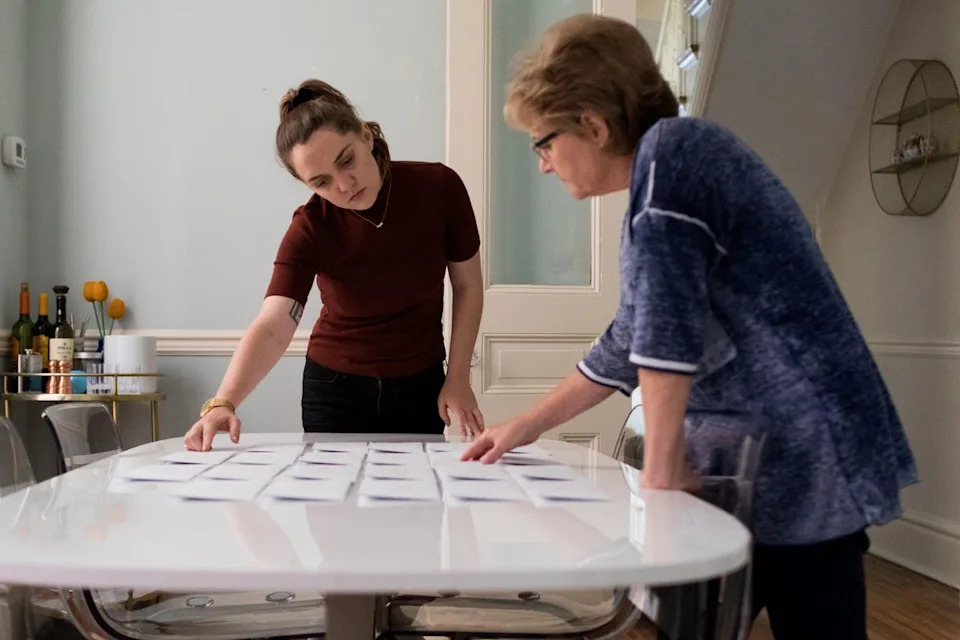

Amanda Mustard spent eight years making an HBO documentary about her grandfather, Dr. William Flickinger, who she and other relatives say sexually abused family members and other children. In a Jan. 8 video op‑ed for The New York Times, Mustard recalled that some people told her she "should have killed" him — a reaction she understands but rejects as a complete response to a complex problem.

Mustard made Great Photo, Lovely Life after the death of her grandmother, Salesta, when she traveled with her mother to Florida to visit Flickinger. A former Pennsylvania chiropractor, Flickinger had a documented history of abuse dating back to the 1970s; he lost his license, was convicted in Florida in 1992 of lewd and lascivious acts against a child, served two years in prison and was required to register as a sex offender.

Rather than seek revenge, Mustard chose to put her grandfather on camera and ask him directly about his actions. While interviewing him at the Florida retirement facility where he was living, she asked whether he had ever been able to open up about what he had done. According to Mustard, he replied, "I wished I could have. I wanted to talk to somebody, but I didn't know who I could really talk to." That exchange convinced her to press for a prevention-focused response to abuse.

"Nothing provokes us like child sexual abuse, and I get it. That rage is totally valid. But my story has taught me that if we really want to protect kids, then we need to confront a painful truth," Mustard told The New York Times.

Mustard highlights two stark facts to argue for change: an estimated 15% of American adults report childhood sexual abuse, and about 90% of survivors were abused by someone they knew. She also points to a striking spending imbalance — roughly $5.4 billion is spent annually on incarceration related to child sexual abuse, while only about $3 million goes to prevention research — and urges greater investment in prevention and evidence‑based reentry programs that reduce recidivism.

Mustard is clear that calling for prevention does not mean excusing perpetrators: she supports criminal accountability but argues punishment alone has not prevented further abuse in some cases. "My grandpa went to prison and nothing changed. He continued to abuse after he was released," she said, underscoring the need for programs that intervene before abuse happens and support people at risk of offending.

Flickinger died in March 2019 at age 86. Mustard says her film was made for survivors who understand the messy, complicated reality of incest and child sexual abuse — not for true‑crime audiences seeking simple villains and tidy endings.

If you or someone you know has experienced sexual abuse, text STRENGTH to 741‑741 to connect with a certified crisis counselor at the Crisis Text Line.

Help us improve.