Sunflower stars (Pycnopodia helianthoides), once common from Mexico to Alaska, were nearly wiped out by sea star wasting syndrome in the mid‑2010s. In September, a California coalition released dozens of captive‑bred juveniles from the "cupid cohort" into Monterey Bay; after one month in protective cages all but one survived and showed no signs of disease. Researchers will continue monitoring with eDNA and direct surveys and aim to scale up releases to help control urchin outbreaks and restore kelp forests.

Sunflower Stars Return to Monterey Bay: Captive‑Bred Sea Stars Reintroduced After Devastating Die‑Off

Divers along the Pacific coast once commonly encountered sunflower stars (Pycnopodia helianthoides), among the largest sea stars on Earth. With as many as two dozen arms that can span more than 3 feet, these manhole‑cover‑sized predators ranged from Mexico to Alaska and helped keep sea urchin populations in check, protecting kelp forests.

A Species Nearly Lost

Beginning around 2013, a mysterious epidemic known as sea star wasting syndrome swept through more than 20 sea star species. The disease caused affected animals to decay and disintegrate; recent research has implicated a bacterium, Vibrio pectenicida, as a likely driver. Sunflower stars were hit especially hard and, after 2017, became rare south of Washington state. The International Union for Conservation of Nature now lists the species as Critically Endangered, and wasting syndrome is estimated to have killed up to 5 billion sea stars overall.

Why Their Return Matters

In the absence of sunflower stars, sea urchin populations have exploded in many places and overgrazed kelp forests. Warming coastal waters linked to climate change have compounded the problem. The Nature Conservancy estimates that up to 96% of kelp forests in Northern California have declined over the past decade. Kelp ecosystems support fisheries and recreation (historically contributing an estimated $250 million annually to California's economy), sequester large amounts of carbon, and provide critical habitat for many marine species.

A Collaborative Restoration Effort

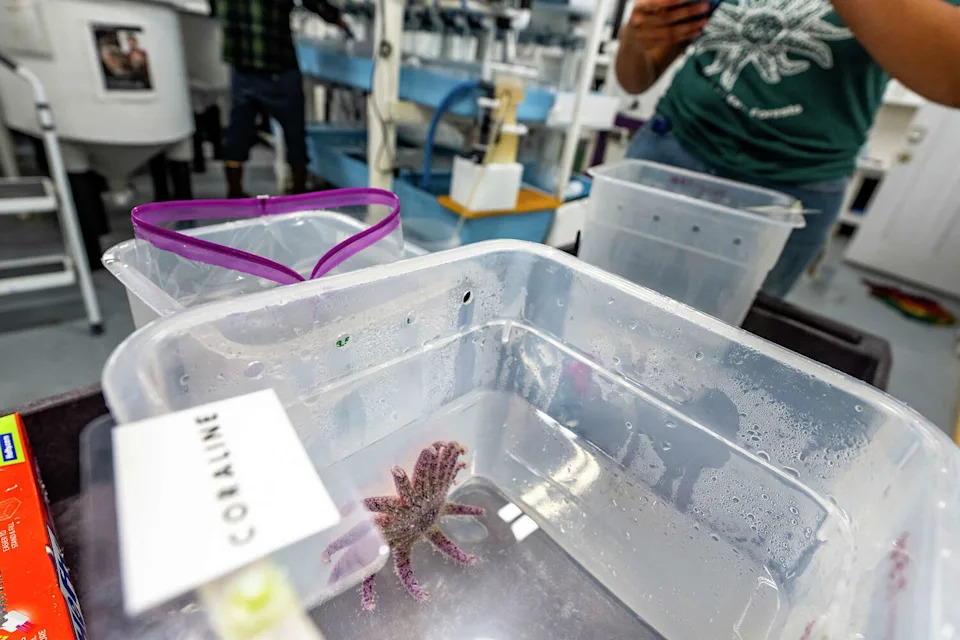

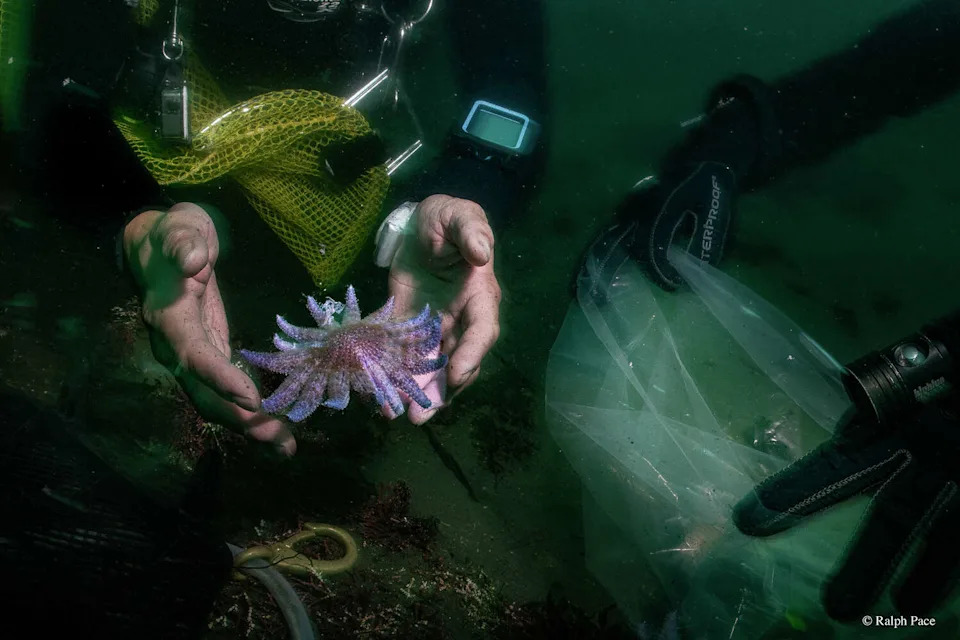

This September, a California conservation coalition — including the Nature Conservancy, Sunflower Star Laboratory, California Academy of Sciences, Reef Check Foundation, Monterey Bay Aquarium, California Department of Fish and Wildlife and Stanford University — released dozens of captive‑bred juvenile sunflower stars into Monterey Bay. All captive sunflower stars in California originate from a single brood called the "cupid cohort," spawned at Birch Aquarium in La Jolla on February 14, 2024.

“The success of this research project is a testament to the collaborative efforts of so many people working together over many years,” said Norah Eddy, associate director of oceans programs at the Nature Conservancy.

Early Trials And Monitoring

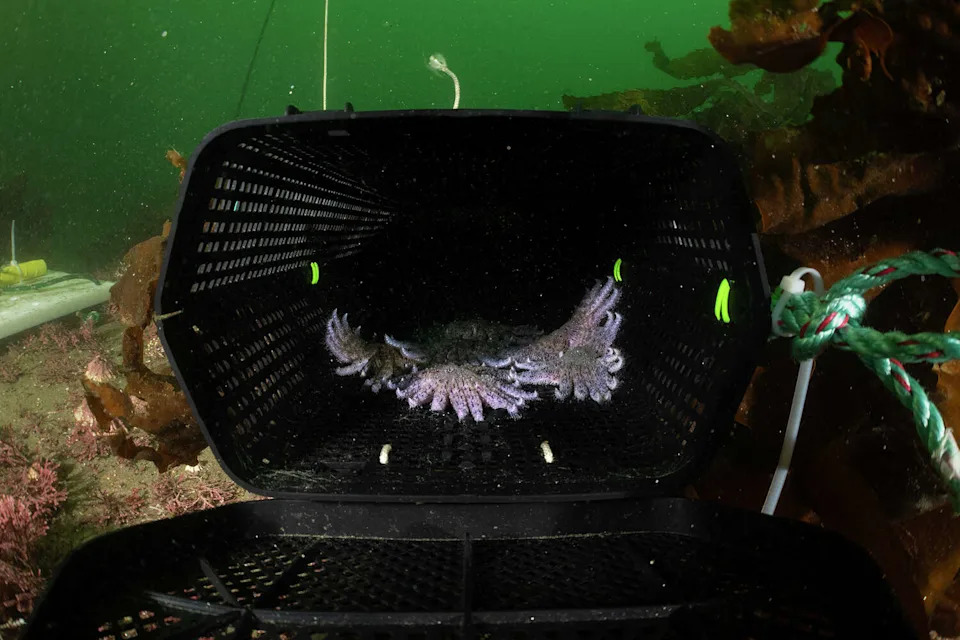

Researchers conducted two small trials in which divers placed the juveniles inside protective cages on the seafloor to monitor survival and disease signs. After one month, all but one of the stars survived; scientists believe the single mortality was likely due to cannibalism. Importantly, none of the released animals showed signs of wasting syndrome during the trial.

Scientists also collected water samples for environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis — a sensitive tool that detects genetic material organisms shed into the environment. Teams will continue to use eDNA and direct monitoring to track the transplanted stars and to screen other sea star populations for lingering disease reservoirs.

Next Steps

The long‑term goal is to scale up reintroductions, potentially transplanting thousands of sunflower stars along the Pacific coast to help restore ecological balance. For now, the juveniles have been returned to laboratory care to grow and be monitored further while researchers refine husbandry and release methods.

“Releasing lab‑raised animals into the wild always carries uncertainty, but this milestone gives us real confidence that we're on the right track,” said Kylie Lev, senior curator at the California Academy of Sciences' Steinhart Aquarium.

Researchers caution that recovery will be gradual and depend on managing disease, continued monitoring, and addressing broader threats to kelp ecosystems, including climate change. Still, these early positive results offer a hopeful sign that sunflower stars might one day help kelp forests recover and rebuild more resilient coastal ecosystems.