3I/ATLAS, an interstellar comet, reached its closest point to Earth last Friday at about 168 million miles (just under twice the Earth–Sun distance) and is now receding. Detected by the ATLAS telescope network in Chile in early July, it has released cyanide, unusually high levels of CO2, and metals such as nickel and iron as solar heating vaporized its ices. This is only the third confirmed interstellar object seen in our system, offering a rare scientific opportunity; it is expected to pass the outer planets and depart the solar system around 2028. The encounter also underscores the value of ground telescopes and the risks posed by expanding satellite constellations to future detections.

Farewell, 3I/ATLAS: Interstellar Comet Recedes after Its Closest Flyby

Our visitor from interstellar space is now heading back toward the deep beyond. Last Friday, the object catalogued as 3I/ATLAS made its nearest approach to Earth — roughly 168 million miles, or just under twice the distance between Earth and the Sun — and is now receding on a solitary path through the solar system.

3I/ATLAS is almost certainly not an alien craft, but its discovery has excited astronomers. The comet could be as old as the Milky Way itself. As sunlight has warmed its ices, instruments have detected the release of cyanide (a common cometary component), unusually large amounts of carbon dioxide, and metallic elements such as nickel and iron. Those signatures, combined with its hyperbolic trajectory, mark 3I/ATLAS as only the third confirmed interstellar object observed in our system (joining 'Oumuamua and 2I/Borisov), making it a rare scientific opportunity.

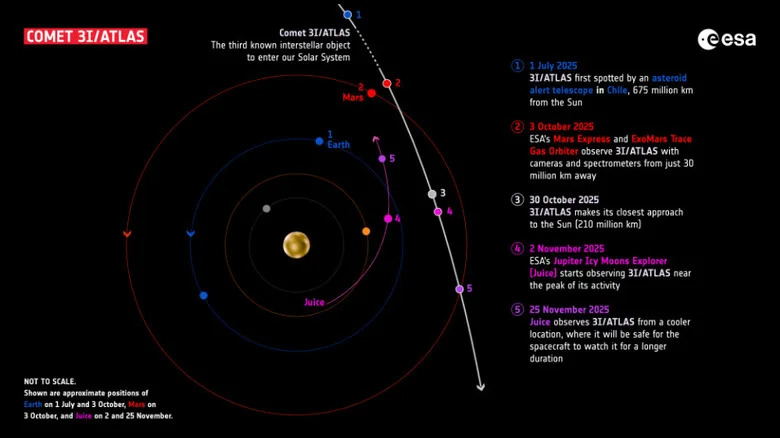

The ATLAS network (Asteroid Terrestrial-Impact Last Alert System) first spotted the object from a telescope in Chile in early July. Trajectory plots shared by the European Space Agency show the relative flight paths: after the initial detection, 3I/ATLAS passed near Mars and then moved behind the Sun from Earth's perspective. By last Friday, Earth’s orbital motion placed us at the point of closest mutual approach with the departing visitor.

Why This Matters

Although the encounter was brief, the data gathered are valuable. Composition measurements help astronomers compare interstellar material to objects formed in our solar system. Planned projections suggest 3I/ATLAS will swing past the outer planets — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune — over the next few years before finally leaving the solar neighborhood around 2028.

ATLAS did what it was designed to do: detect and alert scientists to an incoming object. That success highlights the continued importance of ground-based observatories. If rapidly growing satellite constellations begin to degrade the sky for optical telescopes, our ability to spot future interstellar visitors (or potentially hazardous objects) could be compromised — leaving us with less warning and fewer scientific opportunities.

Farewell, 3I/ATLAS: you came from afar, taught us much in a short time, and now continue your long voyage among the stars.