Biomolecular condensates are membraneless compartments formed when proteins and RNA coalesce into gel‑like droplets, creating localized biochemical environments. About 30 types had been identified by 2022 and they occur in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells, challenging the classic membrane‑bound view of organelles. Driven often by intrinsically disordered proteins, condensates affect our understanding of protein function, the origin of life and neurodegenerative disease research, and are emerging as potential therapeutic targets.

Cells Contain Far More Membraneless 'Mini‑Organs' Than Previously Thought

Cells contain many more membraneless 'mini‑organs' than scientists once believed. Since the mid‑2000s researchers have discovered roughly 30 types of biomolecular condensates — gel‑like droplets made of proteins and RNA that form distinct biochemical microenvironments without a surrounding lipid membrane. These findings are reshaping how we understand cellular organization, protein chemistry and even possible pathways for the origin of life.

What Are Biomolecular Condensates?

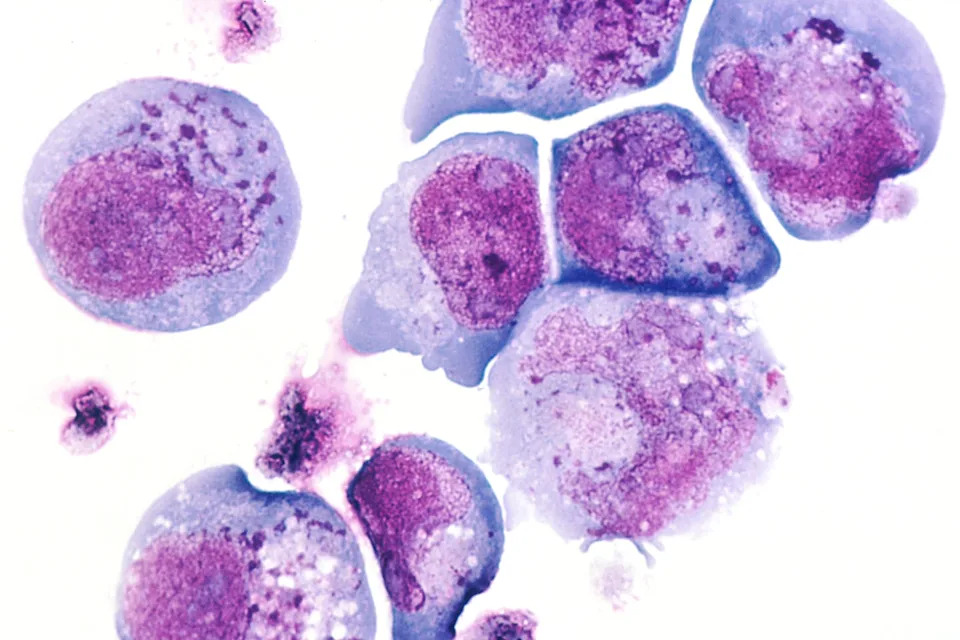

Think of a lava lamp: blobs of wax merge, split and re‑form while remaining separate from the surrounding liquid. Biomolecular condensates behave similarly, except they are composed of proteins and RNA. Certain molecules preferentially interact with one another and coalesce into droplets that concentrate specific biochemical reactions and components, creating a compartment without a membrane.

How They Change Fundamental Biology

For decades biochemists have worked under the maxim 'structure equals function' — that a protein's folded three‑dimensional shape determines what it does. Condensates complicate that story. Many proteins that drive condensate formation contain intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) and are called intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs). These regions lack a stable folded structure, yet IDPs frequently mediate specific interactions and phase separation to form condensates, revealing an alternative mode of molecular organization and function.

Found Across Life — Including Bacteria

Biomolecular condensates are not limited to complex eukaryotic cells. Researchers have identified condensates in prokaryotic (bacterial) cells as well, overturning the notion that bacteria are simply unstructured sacks of biomolecules. Although only about 6% of bacterial proteins contain disordered regions compared with roughly 30%–40% of eukaryotic proteins, several bacterial condensates have been linked to functions such as RNA synthesis and degradation. These discoveries suggest that internal spatial organization is more widespread and ancient than previously recognized.

Implications for the Origin of Life

Studies show nucleotides can plausibly form under prebiotic conditions and can polymerize into short RNA chains. A key question in origin‑of‑life research is how those RNAs could have organized and replicated inside primitive compartments. Because lipids required for membranes may have been scarce on early Earth, the ability of RNA and proteins to concentrate into condensates offers an alternative route for forming protocell‑like compartments without lipid bilayers, making the emergence of organized chemistry a more accessible step from nonliving chemistry.

Links To Disease And Therapy

Condensates are already informing studies of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). In some cases, aberrant phase transitions or misregulated condensates may contribute to protein aggregation and cellular dysfunction. This has spurred interest in therapeutic strategies that modulate condensates — for example, small molecules that stabilize, dissolve or alter condensate composition — though translating these approaches into safe, effective treatments remains an open challenge.

Outlook

As researchers assign functions to more condensates and develop tools to probe and manipulate them, we can expect a deeper and more nuanced view of cellular organization. Over time, many condensates may be given specific functional names and roles, and biology curricula will likely expand to reflect this richer intracellular landscape.

Author: Allan Albig, Boise State University. Funding: The author reports funding from the National Institute of Health. This article was republished from The Conversation.