Researchers found that cycads actively heat their reproductive cones — by up to 27°F — and emit increased infrared radiation that attracts nocturnal beetle pollinators. Experiments using 3-D printed models and infrared-transparent film show beetles detect infrared emission rather than just convective warmth. The team identified TRPA1 gene variants in beetle antenna neurons, providing the first molecular evidence of infrared sensing in beetles. Fossil and database analyses suggest this heat-based signaling is an ancient pollination strategy that predates colorful visual pollinators.

Ancient Cycads Warm Their Cones — Beetles Track the Infrared Signal

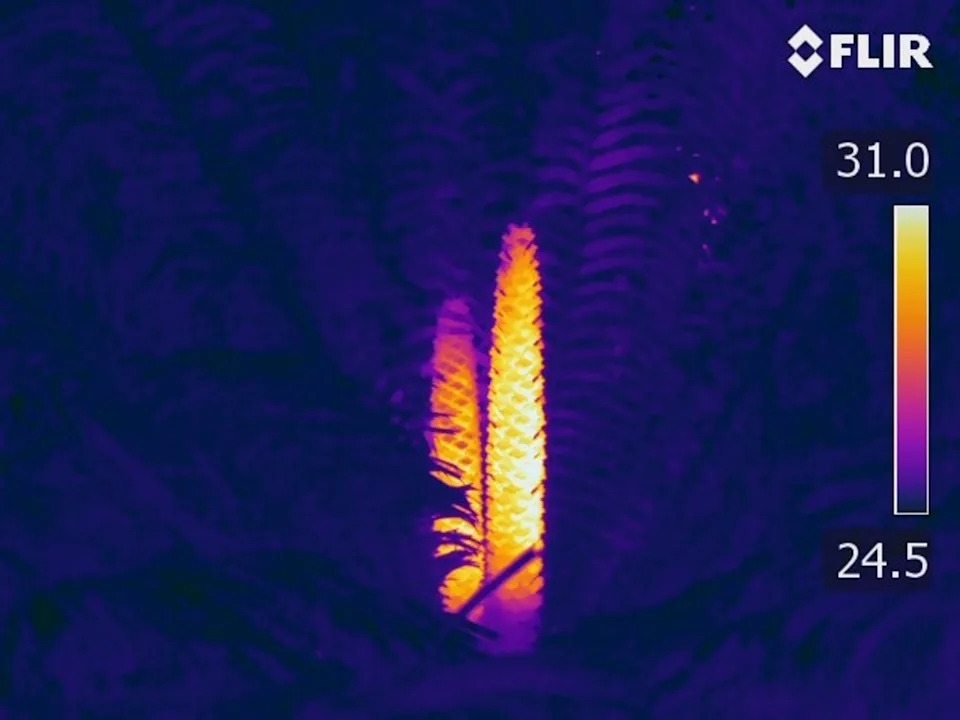

At night in parts of the Amazon, certain seed-bearing plants called cycads actively warm their reproductive cones and emit extra infrared radiation, effectively signaling nocturnal beetles to come and pollinate them. A new study published in Science shows this heat-driven infrared emission serves as a long-range pollination cue — one of the oldest known strategies for plant–insect communication.

How The Signal Works

Cycads can heat their cones by as much as 27 degrees Fahrenheit above ambient air temperature. Male cones, which carry pollen, typically heat up and cool down before female cones do; female cones warm about three hours later. This predictable timing creates a reliable route for beetles to move from pollen sources to receptive female cones.

Behavioral And Lab Evidence

Field and laboratory experiments with the Amazonian beetle Rhopalotria furfuracea showed that beetles prefer the warmest parts of pollen-bearing cones. To test whether beetles were responding to heat itself or to infrared radiation emitted by heated cones, researchers built 3-D printed cycad models and used polyethylene film that is largely transparent to infrared light a short distance from the surface. Beetles were still attracted to heated models even when convective warmth was obscured, supporting the conclusion that infrared emission — not just tactile warmth or airflow — guides the insects.

Sensory Mechanism: TRPA1 In Beetle Antennae

At the molecular level, neurons in the beetles' antennae express variants of the TRPA1 gene. TRPA1 has previously been linked to infrared sensing in other animals, such as some snakes and mosquitoes. Finding related gene variants in beetle antenna neurons provides the first molecular and cellular evidence for infrared sensing in a beetle species and suggests that similar molecular tools have been repurposed across very distant animal lineages.

Evolutionary Context And Broader Implications

Fossil evidence indicates beetle pollination of cycads dates back at least to the early Jurassic, roughly 200 million years ago. Database and fossil analyses in the study also reveal an inverse relationship between seed-plant color diversity and the ability to produce thermal signals: plant families with greater color variation are less likely to heat their reproductive structures and vice versa. That pattern, together with the early diversification of beetles, suggests infrared-based signaling may have been an ancient route to pollination before the rise of visually oriented pollinators such as bees and butterflies.

Not The Only Signal

Infrared emission appears to function as a long-range locator for nocturnal beetles, but it works alongside other cues. Humidity and scent remain important — especially at close range — to attract beetles into cone entrances and toward pollen and other rewards. The researchers plan to test how heat, humidity, and scent interact to guide pollinators in future work.

Because these beetles are nocturnal and lay eggs inside cone structures, their life cycles are tightly linked with cycads — a relationship that likely reinforced this ancient signaling system.

Note: The study includes fieldwork in the Peruvian Amazon, behavioral trials at the Montgomery Botanical Center, genetic and neuronal analyses of beetle antennae, and controlled lab experiments with 3-D printed cycad models. It was published in the journal Science.