New comparative analyses of life-history data for nearly 1,000 mammal species indicate that twin births were likely the ancestral condition for primates, with the common ancestor around 60 million years ago typically producing two offspring. At least 50 million years ago, many primate lineages independently shifted to single births—a transition the authors link to reduced maternal energetic costs and the evolution of larger brains and bodies. Modern twin rates have risen in places like the U.S. due to assisted reproductive technologies and older maternal age, but twin pregnancies carry higher risks such as prematurity.

Study Finds Twin Births Were Likely the Primate Norm — Singletons Evolved Later

Twin births have long captured human imagination—symbolizing vitality, duality and myth. New comparative research suggests that, far from being an oddity, birthing two offspring at a time may have been the ancestral condition for primates. Over deep evolutionary time, many primate lineages independently shifted toward single births, a change the authors link to the evolution of larger bodies and brains.

What the Researchers Did

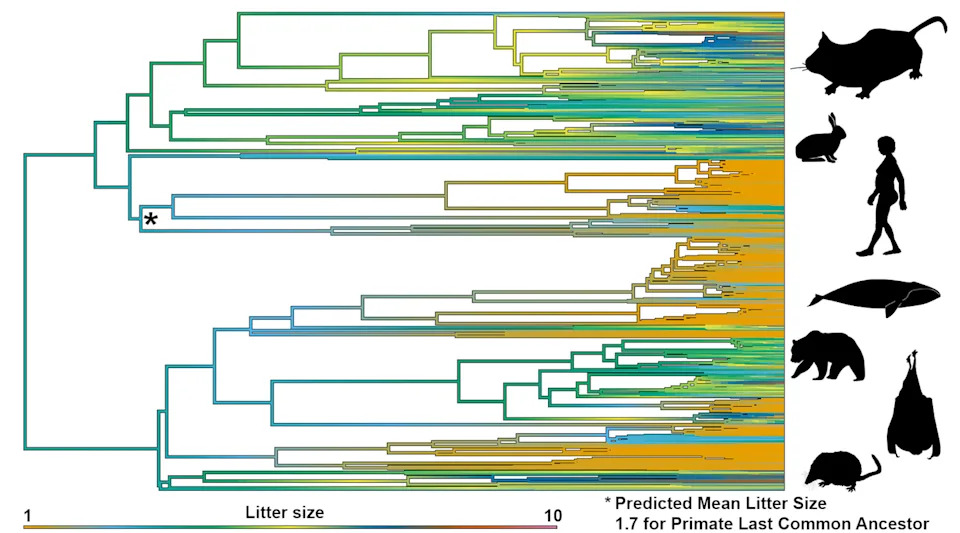

The team compiled life-history data for nearly 1,000 living mammal species from public sources (including AnAge) and recorded traits such as typical litter size, newborn and adult body mass, and gestation length. Because fossil skeletons rarely preserve direct evidence of litter size, the authors used those comparative data and evolutionary modeling to estimate the most likely litter sizes of mammalian and primate ancestors.

Key Findings

Modeling indicates the most recent common ancestor of primates—living in North America roughly 60 million years ago—likely produced twins as the typical litter. The shift from twin-bearing to singleton-bearing lineages appears to have occurred at least 50 million years ago and took place independently in multiple primate groups. This repeated, convergent pattern suggests single births conferred selective advantages under certain ecological or energetic conditions.

Why Singletons May Have Been Favored

Multifetal gestation places greater energetic demands on mothers and tends to produce smaller, often earlier-born young. Producing one larger offspring allows for longer in-utero development and greater neonatal size and maturity—traits that would support extended learning and developmental plasticity. The authors argue that this reproductive shift helped pave the way for increases in body and brain size (encephalization), especially in the human lineage.

Relevance to Humans and Modern Twin Rates

Modern humans overwhelmingly give birth to single infants. Human babies are relatively large with disproportionately large heads, and extended childhood learning is central to our species’ life history. Today, twin birth rates have risen in some countries (for example, roughly doubling in the United States over the past 50 years), driven in part by assisted reproductive technologies and older maternal age. Currently about 3% of U.S. live births are twins, though recent trends show a modest decline.

Health Considerations

Twin pregnancies carry higher clinical risks: in the U.S., more than half of twins are born prematurely and many require neonatal intensive care. The paper emphasizes that, while twin-bearing was common in deep primate history, modern social, medical and environmental contexts make twin births a different experience today.

Limitations and Notes

The study infers ancestral litter sizes indirectly through comparative data and statistical models; direct fossil evidence of litter size is extremely rare. The authors acknowledge corrections to the list of extant mammals that commonly produce twins. One author, Tesla Monson, also notes a personal perspective as the mother of twin girls. Funding and affiliations are disclosed: Tesla Monson (Western Washington University; support from the Leakey Foundation, NSF, and Western Washington University) and Jack McBride (Yale University; previously affiliated with Western Washington University).

Bottom line: Comparative life-history modeling indicates twins were likely common among early primates, and multiple independent evolutionary shifts toward singleton births occurred—changes that may have contributed to the evolution of larger brains and bodies, including in humans.