Scientists estimate a better-than-99% chance California will experience at least one magnitude 6.7+ earthquake in the next 20 years, while the statewide chance of a magnitude 8 quake is about 7%. The Hayward Fault poses the single biggest Bay Area risk (14% for M6.7+ by 2043; ~33% combined with Rodgers Creek). Other notable risks include Calaveras, San Andreas, San Jacinto and Elsinore. Experts stress the forecast is approximate and urge residents to prepare for more likely medium-size quakes by securing homes, building emergency kits and signing up for ShakeAlert.

Which Fault Line Are You On? A Clear Guide to California’s Earthquake Risks

Drop. Cover. Hold on. That simple jingle is the basic safety reminder every Californian learns for living in earthquake country.

Scientists estimate there is better than a 99% chance California will experience at least one earthquake of magnitude 6.7 or greater within the next 20 years, though they cannot predict exactly when or where such an event will occur. The statewide chance of a magnitude 8 quake — near the size of the 1906 San Francisco event — is much lower, roughly 7%.

California lies along the boundary between the Pacific and North American tectonic plates. The Pacific Plate creeps northwest at about 2 inches per year, building strain on faults where sudden slips produce earthquakes. To help communities plan, scientists produced a 30-year earthquake-rupture forecast in 2014 that models likely magnitudes, locations and probabilities of damaging quakes and explicitly accounts for how "ready" a fault is to rupture.

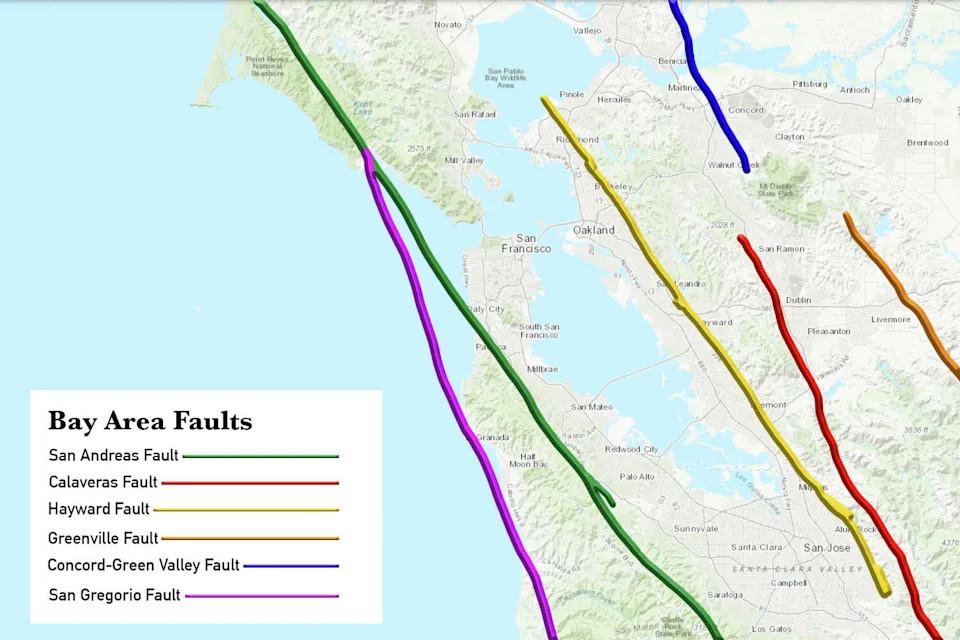

Northern California: Bay Area Faults

The Hayward Fault is considered the single most likely Bay Area source of a significant quake. It runs roughly 75 miles from San Jose north to San Pablo Bay and lies under or very near communities including Milpitas, Fremont, Hayward, San Leandro, Oakland, Berkeley and Richmond. The 2014 forecast gives Hayward about a 14% chance of producing a magnitude 6.7-or-greater earthquake by 2043; if combined with the Rodgers Creek Fault just to the north, that combined chance rises to roughly 33%.

Historically, the last major Hayward event was about magnitude 7 in 1868, which damaged buildings across the East Bay and as far away as San Francisco and Napa. UC Berkeley seismologist Roland Burgmann estimates the Hayward Fault ruptures on average every 150 years, plus or minus about 50 years, and notes the fault is currently considered a significant hazard.

The Calaveras Fault, which links to Hayward, carries the forecast's second-highest Bay Area probability: about 7.4% for a 6.7-or-larger event by 2043. Calaveras runs from near Danville toward San Benito County, passing through or near Dublin, Pleasanton, Sunol, San Jose and Morgan Hill. Small earthquake swarms have recently occurred near San Ramon but so far have not triggered a major rupture.

The San Andreas Fault — famous worldwide — threatens both northern and southern California. In the Bay Area the forecast assigns it about a 6.4% chance of producing a 6.7-or-greater quake by 2043. The San Andreas produced the devastating 1906 San Francisco quake (estimated by the USGS at about magnitude 7.9), and while a repeat of that size would be very consequential, experts say such an event remains relatively rare.

UC Santa Cruz physicist Emily Brodsky highlights a low-probability but high-impact "nightmare" scenario: if an overdue southern San Andreas rupture were to jump across the currently creeping central section, it could produce a very large event spanning from near the Mexican border up toward Mendocino County.

Southern California: Multiple Strands

In Southern California the plate-boundary system branches into several strands. The San Jacinto Fault — part of the same system — has about a 5% chance of producing a magnitude 6.7-or-greater quake by 2043. It begins near Cajon Pass and runs southeast through San Bernardino, Riverside and Imperial counties. The Elsinore Fault carries roughly a 3.8% chance for a similar-size event.

Scientists also note other concerns: offshore faults can be harder to monitor, geothermal operations have in some cases induced earthquakes, and a very large quake outside California (for example along the Cascadia subduction zone) could in some circumstances influence stress on California faults.

What The Forecast Means — And What You Can Do

Experts describe the 2014 30-year forecast as a useful but approximate model. Some major recent quakes — the magnitude-6.9 Loma Prieta event (1989), magnitude-6.7 Northridge (1994) and magnitude-6.0 Napa (2014) — occurred in places that were not the highest-probability targets in the forecast. There is always an element of surprise in earthquake hazard.

Instead of fixating on rare, extreme events, seismologists urge Californians to prepare for the more likely medium-size quakes (magnitude 5–6) that cause most everyday damage. Practical steps include securing heavy furniture and appliances, strapping water heaters, preparing an emergency kit with food, water and medications, planning family meeting points, and signing up for early-warning services such as ShakeAlert.

For official guidance, see the USGS for earthquake safety and kit checklists and the California Department of Public Health for general emergency preparedness advice.

Key sources: U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) 30-year earthquake rupture forecast (2014); interviews with seismologists Roland Burgmann and Emily Brodsky; USGS historical summaries.