The Bodrum Peninsula preserves the remains of many civilizations, most notably the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, built around 350 BCE for Mausolus and completed by his sister‑wife Artemisia II. Once one of the Seven Wonders, the tomb combined Greek, Egyptian and Lycian styles and was adorned with hundreds of sculptures. Earthquakes destroyed it centuries later; excavations recovered fragments now displayed locally and in major museums. Nearby sites — an antique theatre, Myndos Gate, Bodrum Castle, Labraunda and Pedasa — reveal the wider story of Caria’s ancient past.

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus: A Love, Power and a Lost Wonder

The Bodrum Peninsula rises from the Aegean with forested peaks and white, flat‑roofed homes clinging to its slopes. Its sheltered bays now host luxury villas and gulet‑filled marinas, but beneath the seaside leisure lies an extraordinary archaeological past.

At the heart of that history stands the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, built around 350 BCE for Mausolus and completed by his sister‑wife, Artemisia II. Commissioned by the ruling Hecatomnid family of Caria, the tomb became one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World — a lavish fusion of Greek, Egyptian and Lycian architectural and sculptural traditions.

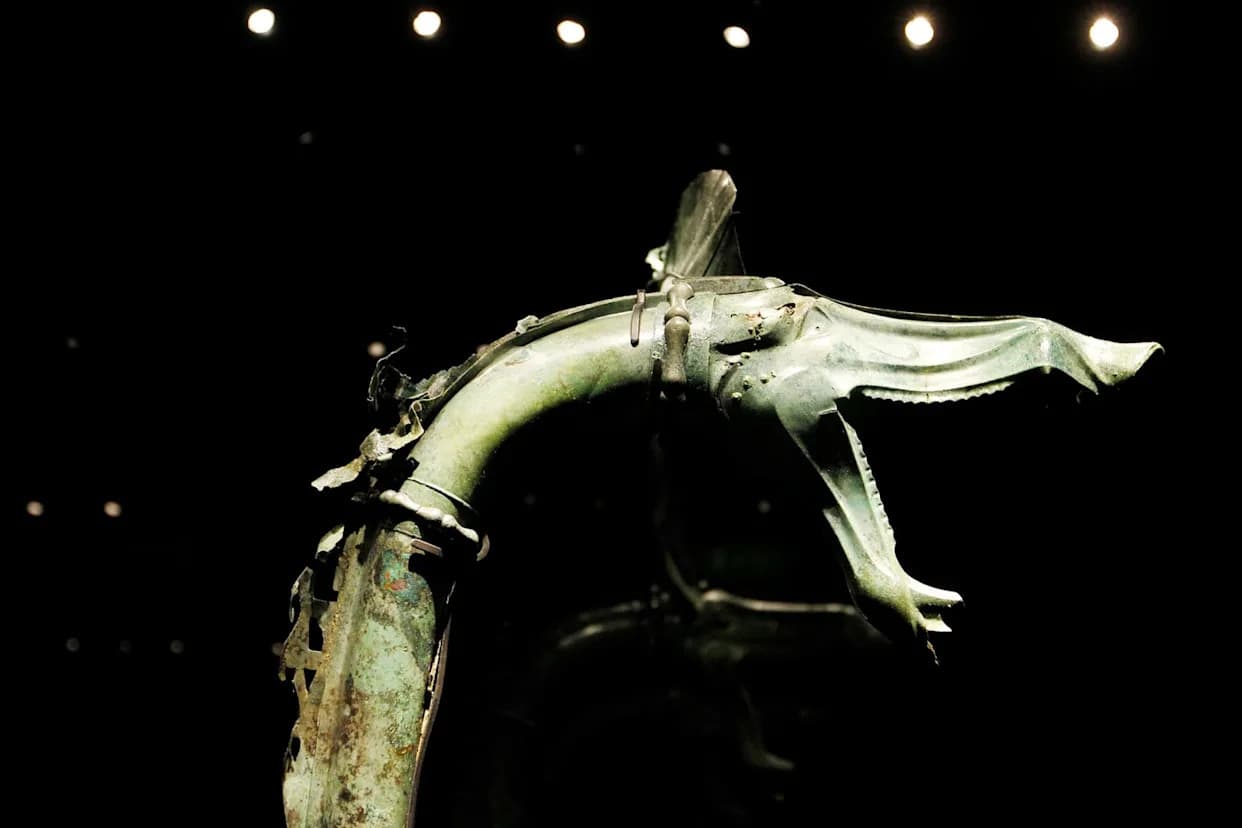

Artemisia supervised an elaborate structure: a broad, columned base more than 400 feet in circumference, richly decorated with battle friezes and nearly 400 free‑standing sculptures, and capped by a stepped pyramid crowned by a four‑horse chariot carrying statues of the couple. Local tradition says Mausolus was cremated and that Artemisia mourned him intensely; later legends even claimed she drank his ashes mixed with wine.

Centuries of earthquakes — particularly between the 12th and 15th centuries — brought the monument to ruin. In the 19th century British archaeologist Charles Newton excavated the sunken foundations now visible at the Bodrum Mausoleum archaeological park, revealing the burial chamber, drainage works and fragments from the original 36 columns. Major sculptural pieces were taken to the British Museum, while the site and its small park museum display other recovered fragments.

Walk the ancient city

Short walks from the mausoleum lead to a cluster of related sites that help reconstruct life in ancient Halicarnassus. The horseshoe‑shaped Antique Theatre, begun under Mausolus and expanded by the Romans, once seated up to 10,000 people for plays, gladiatorial contests and animal fights; today it hosts concerts and cultural events for smaller crowds.

Close by, the Myndos Gate survives as a testament to the city’s fortifications. Built of andesite, its massive bases have endured for roughly 2,400 years, and a nearby necropolis contains Roman and Hellenistic vaulted tombs. A poignant remnant of ancient warfare is a 23‑foot‑wide, 8‑foot‑deep moat that helped repel Alexander the Great’s forces during the siege of 334 BCE.

Overlooking the bay is Bodrum Castle, a 15th‑century fortress built by the Knights of Saint John and later modified under Ottoman rule. The castle stands on the promontory believed to have held Mausolus’s palace and incorporates marble columns and stone salvaged from ancient ruins. Today it houses the Museum of Underwater Archaeology and exhibits that trace the region’s Mycenaean, Carian, Hellenistic and later histories.

People and practices

The Hecatomnid dynasty was unusual: two sibling pairs married (Mausolus and Artemisia; Idrieus and Ada). These unions, rare and often taboo elsewhere in the Greek world, likely aimed to preserve dynastic continuity and mirror divine sibling unions found in myth. Ada, thought to be the ‘‘Carian Princess’’ whose sarcophagus was recovered in 1989 at Yokuşbaşı, later ruled Caria and was briefly reinstated with the support of Alexander the Great.

Mausolus’s rule left tangible traces: temples, defensive walls and civic monuments. Local guides note colorful anecdotes — such as a tax on men’s long hair, allegedly used to make wigs for elites — that speak to the era’s fiscal pressures and cultural intersections between Persian and Greek influences.

Explore beyond Bodrum

Beyond the town, quiet hills and coastal villages preserve hidden ruins. Pedasa, an ancient settlement reachable by a few miles’ hike, was depopulated by Mausolus to strengthen Halicarnassus. Labraunda — a remote mountain sanctuary of Zeus largely developed under Idrieus — rewards visitors with dramatic terracing and rock‑cut remains. The Carian Trail, a long‑distance route across the region, links these sites and offers stretches of solitude despite Bodrum’s popularity.

On the western coast, Gümüşlük’s shallow waters reveal the so‑called King’s Road at low tide, an ancient causeway that leads toward Rabbit Island — the submerged tip of Myndos, founded by the Lelegians millennia ago. Excavations continue, and much of the ancient city remains beneath the sea and town.

Where the pieces ended up

Many of the Mausoleum’s sculptural masterpieces reside today in museums — notably the British Museum, where lions, battling friezes and colossal figures of Artemisia and Mausolus are displayed. These sculptures, more than two millennia from their original setting, still convey the grandeur and ambition of a monument built to immortalize a ruling couple.

The ruins and museums around Bodrum offer visitors a layered experience: a reminder that political ambition, artistic achievement and human grief created one of antiquity’s greatest wonders — and that even the grandest monuments are vulnerable to time and nature.

Help us improve.